Textile art is having its moment, and it is a global phenomena. As the traditional ‘art-or-craft’ barriers are upended by artists and collectors alike, textile art, (often termed fibre art in the USA where artists in the 1960s and 70s were hugely influential in driving it's acceptance) which can include weaving, crochet, loose thread, carpets, hand and machine stitch and more, is at the forefront of ‘What to Collect Now’. Establishments within architecture, fashion, design and contemporary art continue to take note and comment on the advancement of textile art, it's increasing prevelance in major exhibitions and museums since the 1960s and its particular prominence in the past five years.

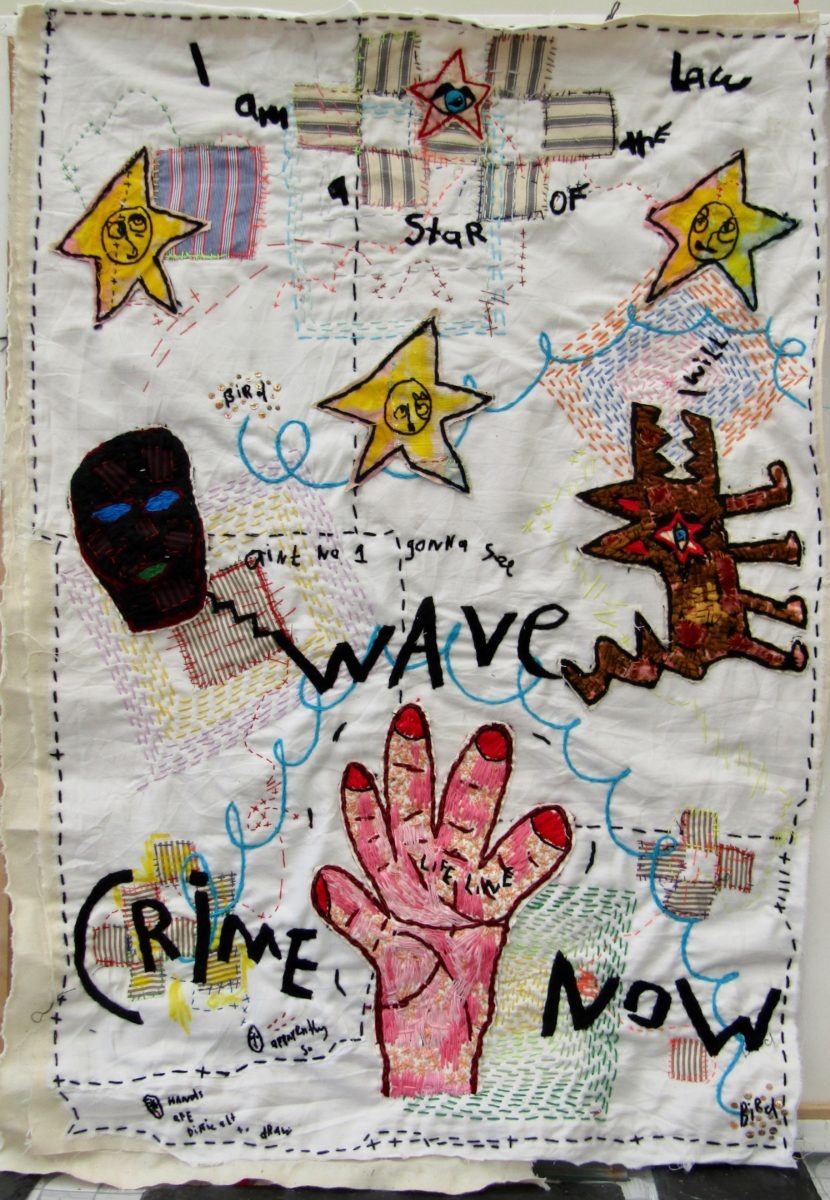

Hands are hard to draw, 2018 by Anthony Stevens

It is not the first time in human history that textile art has been highly sought after, but it has a turbulent history of acceptance and denial. While it has existed for millennia, it has not always been held in such high esteem by the art establishment. Positioning it within a quick potted history helps to understand.

'Fine Lines' by Jacy Wall, 2019

Woven tapestry, wool, linen on cotton warp

Anthropologists estimate that people have been creating and decorating textiles, initially clothes and carpets for warmth, for 100,000-500,000 years. From these humble beginnings where plant and animal fibres would have been spun or twisted together to make functional objects, the journey becomes aligned with our political history.

The 14th-17th centuries in Europe saw wealthy patrons commissioning tapestries, a time when tapestry was often the costliest and most prestigious item in Medieval or Renaissance homes. Medieval English embroidery known as Opus Anglicanum was prized around the world for its skill and artistry. Made by both women and men, it signified the pinnacle of luxury in Medieval Europe. Simultaneously, in the Middle East they made beautifully crafted rugs using symbols and complex designs.

Beneath the Tree, 2019 by Alice Kettle

The Industrial Revolution (1760-1820) and associated burgeoning of affordable fabrics and machine production saw a plethora of textiles as functional objects. Stitching remained associated with the manual work of mainly women. During this period, in 1768, the Royal Academy of Art, London was founded. Eighteen months later it ruled that needlework was not permitted to be shown in the Academy, a damning indictment that textiles were not at the time regarded as high art, undeniably consolidating the prejudice and gender politics of this judgement. During this period of history, textile art fell from favour.

The years following the Second World War saw textile art start to meet its aesthetic and political potential. Used for political purposes and as a means of communication and expression, artists started to work with textiles in ways never previously seen. Visionary creatives moved beyond weaving, and began knotting, twining, plaiting, coiling, pleating, lashing, and interlacing and started exploring the 3D potential of textiles. Textile art started to enter the domain of scholarly writings and academia. By incorporating emotion, message and meaning into the work, artists elevated the status of their work – it had become high art once again. It was a time when the quality of idea and execution was what mattered, not the fabric used. Textile art is a powerful tool for communication which defies boundaries, this has contributed to the democratisation within the art and craft revolution.

The Challenge, 2017, handwoven tapestry by Caron Penney

Championed by women artists in the first half of the 20th century, with two important figures being Annie Albers and Sheila Hicks, textile art is territory now occupied by both men and women, leading to the emergence of some contemporary names including El Anatsui, Chris Offili and Damien Hirst. Prominent names who have become specialists in textile art include Alice Kettle (UK), Anne Wilson (USA) and Hiroyuki Shindo (Japan). Textile art has been surging in popularity with both collectors and artists since the 1960s. An important global event was the Tapestry Biennale in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1962. Today, new younger artists are interested in process, expression and experimentation, and the choice of material is of little significance, they are not confined by outmoded prejudice. Contemporary artists are pushing the medium to its limits. Artists are pushing the boundaries of what is textile and how textiles can be art.

So why is textile art trending now? Its earlier suppression allows it to be new, and therefore exciting. As it has been marginalised historically, it now has a chance to be seen as current and original. There is not a recent abundance of textile art, and with the time it takes to produce, neither is there an oversupply. This form of artistic expression allows designers, architects and artists to incorporate textile art in the spaces of today in unprecedented ways. Textile art is now hung in homes with fine art collections, and museums are acquiring major textile works for their permanent collections. For example, Southampton City Art Gallery, the Museum Partner of London Art Fair 2020, have recently acquired Odyssey, a seminal work by Alice Kettle. Kettle is one of a number of artists showing as part of Threading Forms, a curated section at London Art Fair 2020 attempting to bring to the fore a selection of galleries and artists who are both embracing the potential, and challenging the limitations, of thread in contemporary art. The section of the Fair aims to capture the breadth of different artists working in textiles and the growing appreciation of the medium as a beautiful and collectible art form.

But there is another reason why textile art is coming into its own. In a time of high consumerism and production, with the immediacy of digital, the painstaking handmade object has become a luxury. As millennials demand experiences not things, they can savour the experience of feeling a textile object and contemplate its creation. Textiles are part of all of our lives; we all experience textiles every day, they are familiar and essential. The time taken to stitch or weave is a comforting counterbalance to our rushed lives, soothing our frenzied minds.

About the author;

Candida Stevens is the founding director of Candida Stevens Gallery, a curation-led gallery established in 2014. Threading Forms is showing as part of London Art Fair on 22 – 26 January 2020 (VIP Preview 21 January). https://www.londonartfair.co.uk/

Arusha Gallery show work by Julie Airey

Atelier WeftFaced show work by Caron Penney and Katharine Swailes

Candida Stevens Gallery show work by Alice Kettle

Cavaliero Finn show work by Jacy Wall alongside ceramics by Björk Haraldsdóttir

Oxford Ceramics Gallery show work by Peter Collingwood

OutsideIn show work by Anthony Stevens

West Dean College weave on site throughout the fair

OutsideIn shows the work of Anthony Stevens

West Dean Tapestry Studio will be on site demonstrating weaving all week