Left brain, right brain: whatever the differences between artists and scientists, they share one thing in common - a questioning mind.

Irene Lees never stops questioning things, which may seem surprising in a working class woman who spent most of her life as a wife and mother. But all the while the questions must have been brewing, because she took herself off to do a Diploma in Art and then on to University in her sixties – a time when most people are contemplating retirement – they’ve been bubbling to the surface.

It began with fast fashion. Twelve years ago, when the fair trade clothes shop she used to patronise in Bristol was put out of business by the opening of a branch of Primark, she found herself asking how women in the west could bargain down the prices of garments sewn with sweat and tears by female workers in the Third World. In her graduation year she started making large monochrome drawings of empty dresses, following the thread of her thought over the paper in a continuous drawn line: “I used knitting in my mind as a metaphor for life; if you make a mistake in life you can’t correct it,” she explains. Three of those drawings were immediately selected for Jerwood Drawing Prize, the Cheltenham Art Prize and the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition.

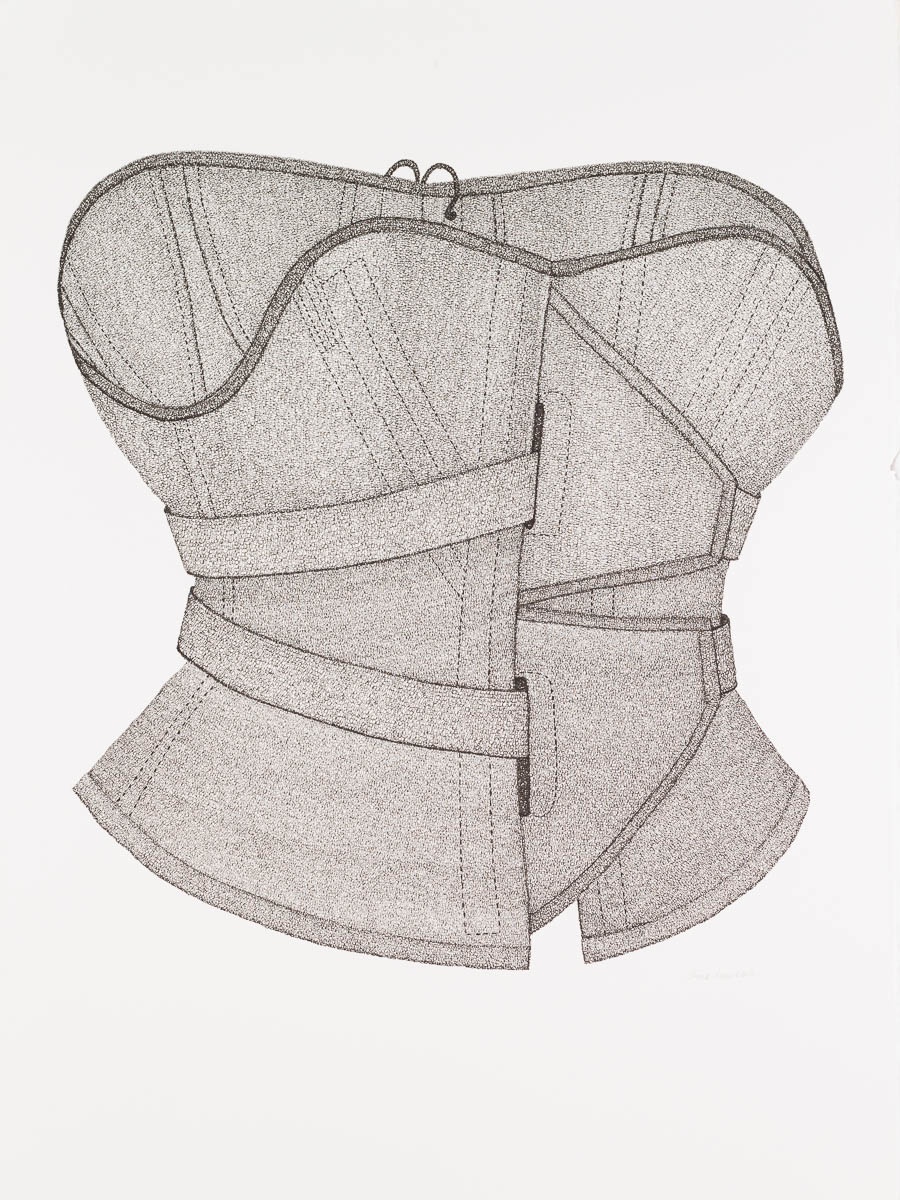

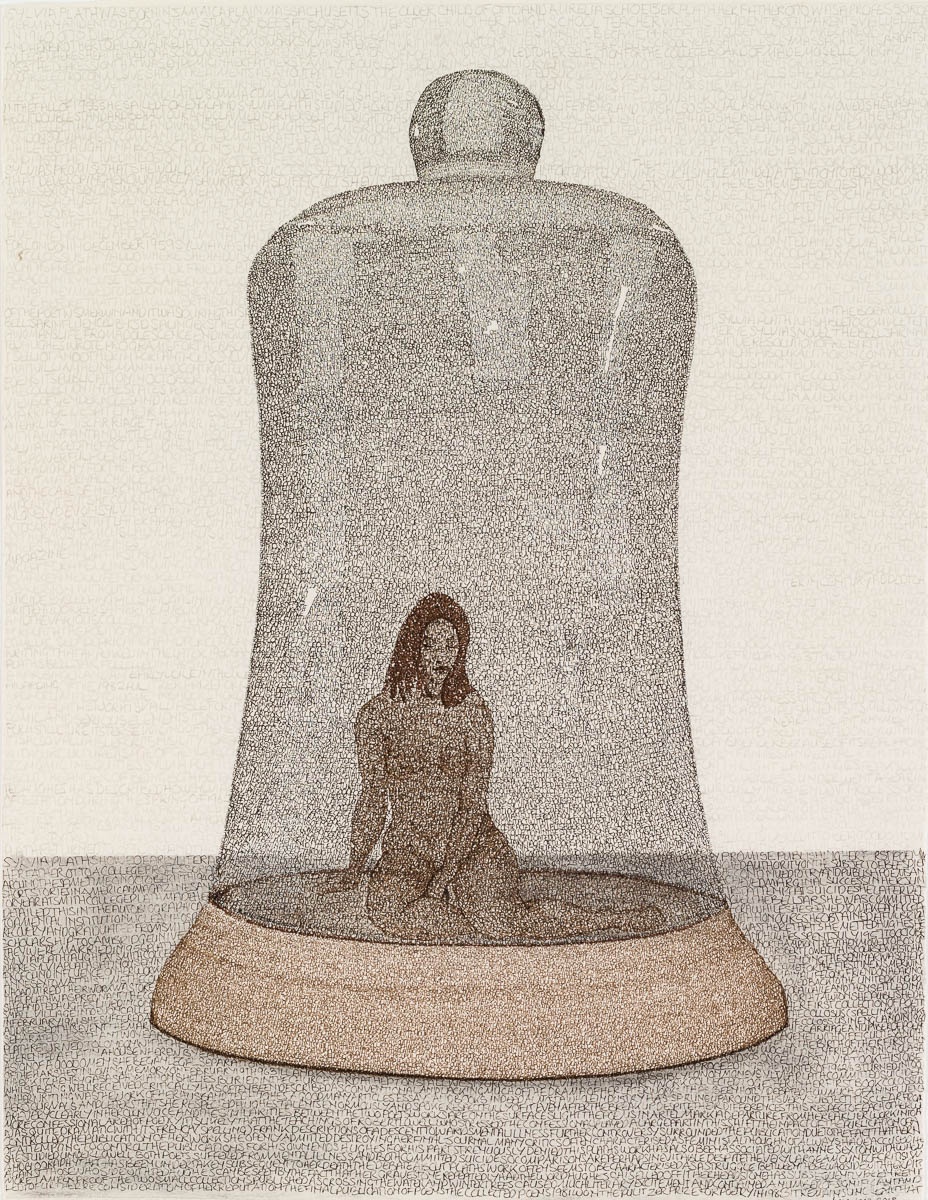

The knitting metaphor got more complicated when her questions began to involve historical research. Curiosity about why women have willingly imprisoned their bodies in corsetry led her to the library of the V&A, where reading about the social history of underwear she found she could memorise passages of text. This gave her the idea of incorporating explanatory text in her work. Without so much as a preparatory pencil outline she found she could draw a corset with a continuous line of writing, winding the text round and round within the form until it was filled with a fine mesh of letters. The resulting images were wrapped in a veil of meaning that could theoretically be unravelled by following the thread of text with a magnifying glass, just as the meaning of Leonardo’s backwards writing can be deciphered by holding a mirror to the page.

Leonardo, too, was an obsessive questioner, though his obsession was with the workings of the natural world; Lees’s obsession is with human psychology and social history. Where she senses social injustice she will pick up a thread and follow it to the source of the trouble, like Theseus tracking the Minotaur through the maze. Her drawings are a record of these journeys, charged with the emotions felt en route. In contemporary conceptual art research can easily be uncoupled from visual imagination, but Lees’s work is a perfect fusion of the two as she literally weaves the research into the image. Her work is conceptual in the true sense of the word: “Every time I’m doing something, it has to have a meaning.”

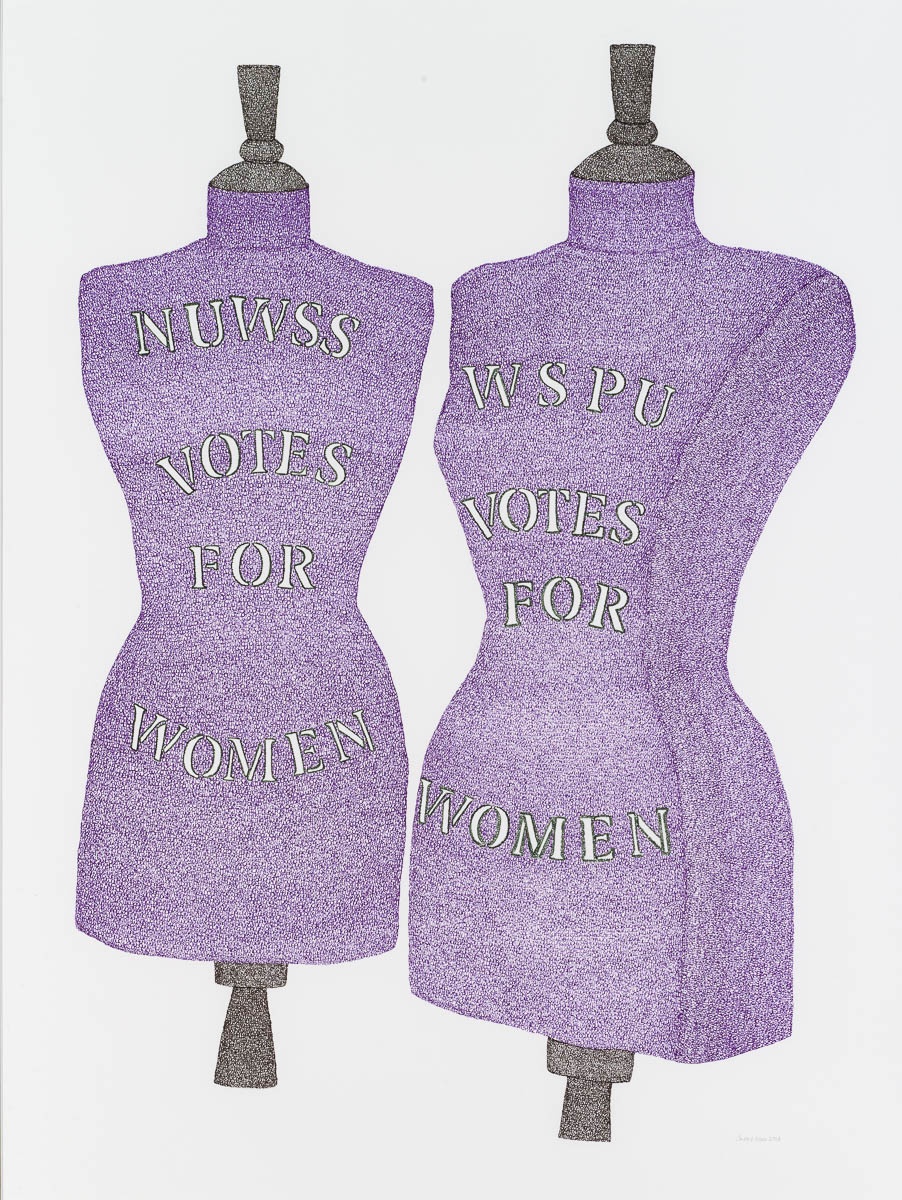

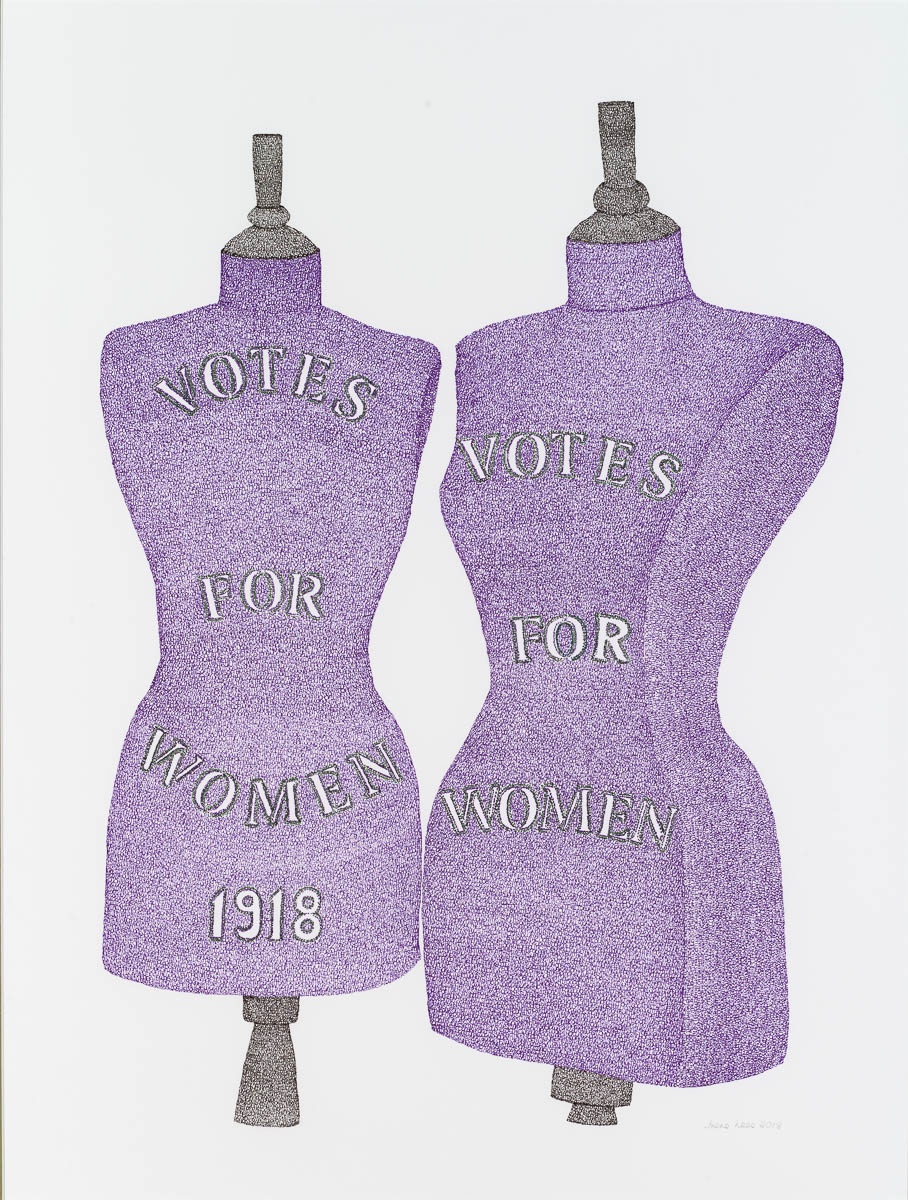

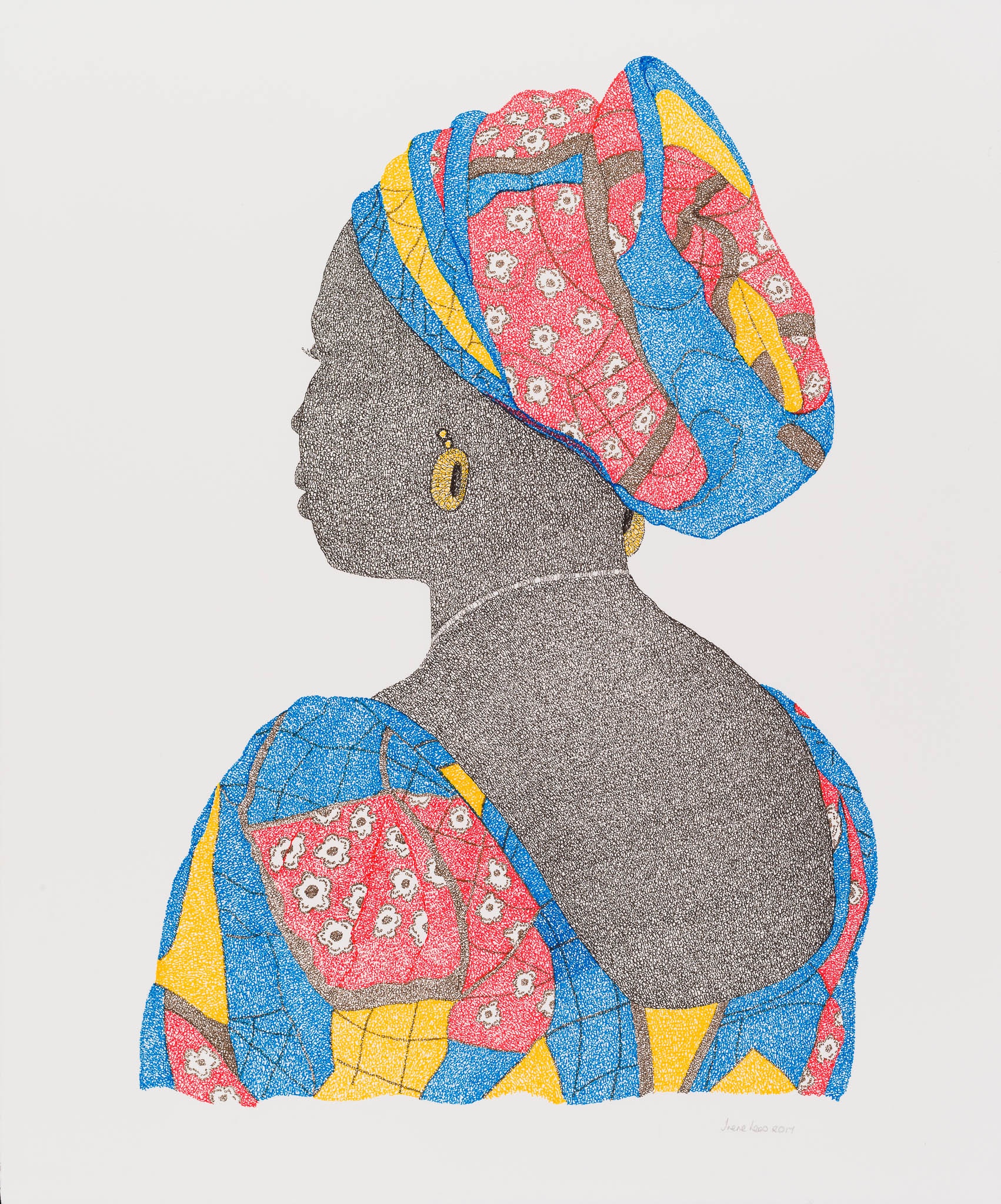

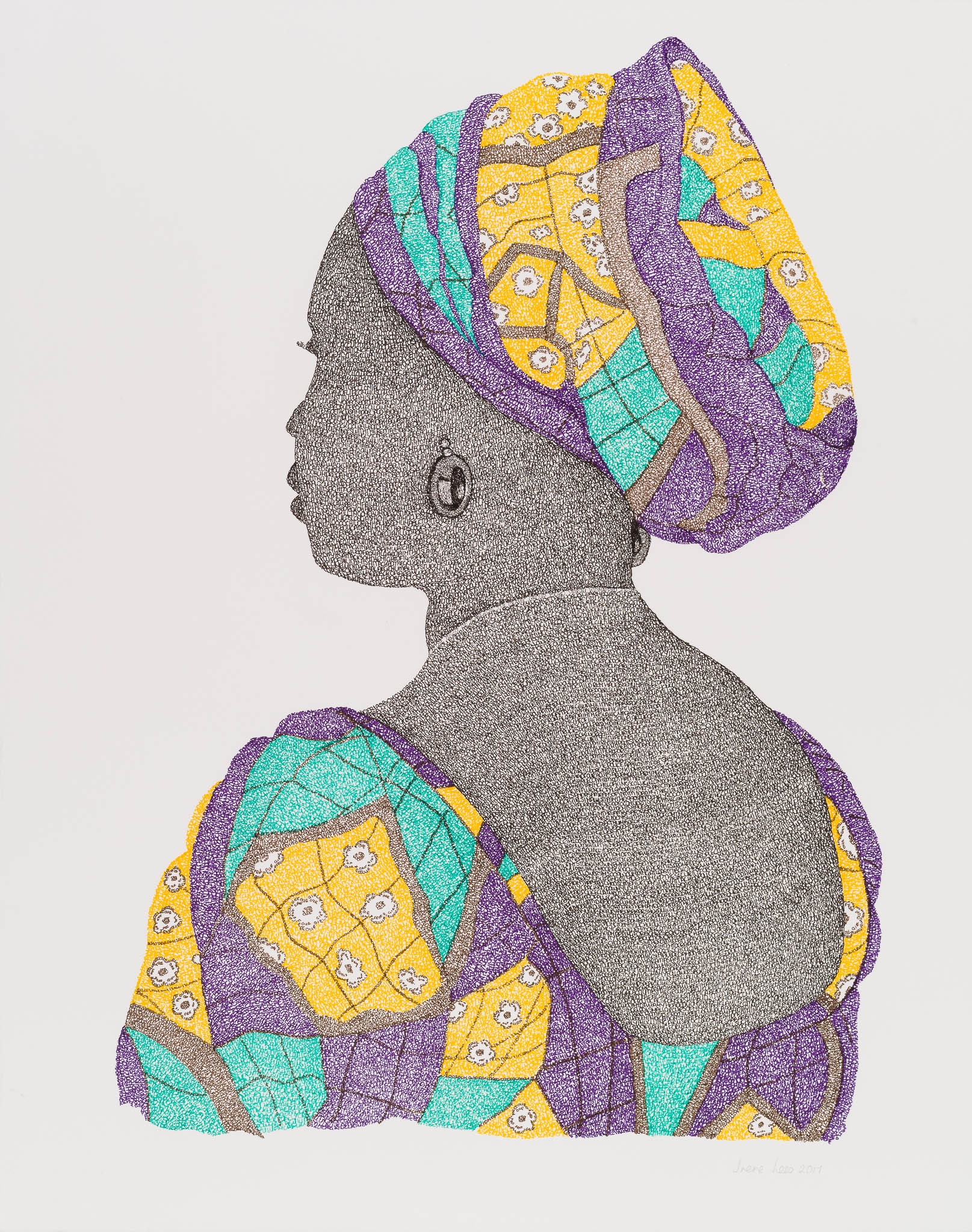

In a recent series celebrating the dignity and fortitude of the mothers of the Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram, colour made its first appearance in her drawings, brightening the patterned fabrics worn by the women. Injustices borne by women are a constant concern for a female artist “brought up in an environment… in which it was understood that life’s raison d’être, as far as women were concerned, was to serve the men, cook, wash and clean, and rear the children.” Returning to her hometown of Oldham recently, she was reminded of local suffragette Annie Kenney who worked in the same mill as her grandmother. The memory inspired a new drawing of a pair of tailors’ dummies upholstered in the purple livery of the Women’s Social and Political Union with VOTES FOR WOMEN emblazoned on their chests. The drawing is titled, pace Churchill, Never Have So Many Owed So Much to So Few.

The origins of her new Bell Jar series lie further back, in a visit to the grave of Sylvia Plath in Heptonstall in the 1970s, when Lees, then a mother of four young children, struggled to fathom how a woman could kill herself and leave her children behind. In one drawing, a nude Plath stands suffocating under a glass bell jar; in another, a split fig evokes her vision of sitting in the crotch of a fig tree starving to death, unable to choose which fruit to pluck lest it close off all other female career options.

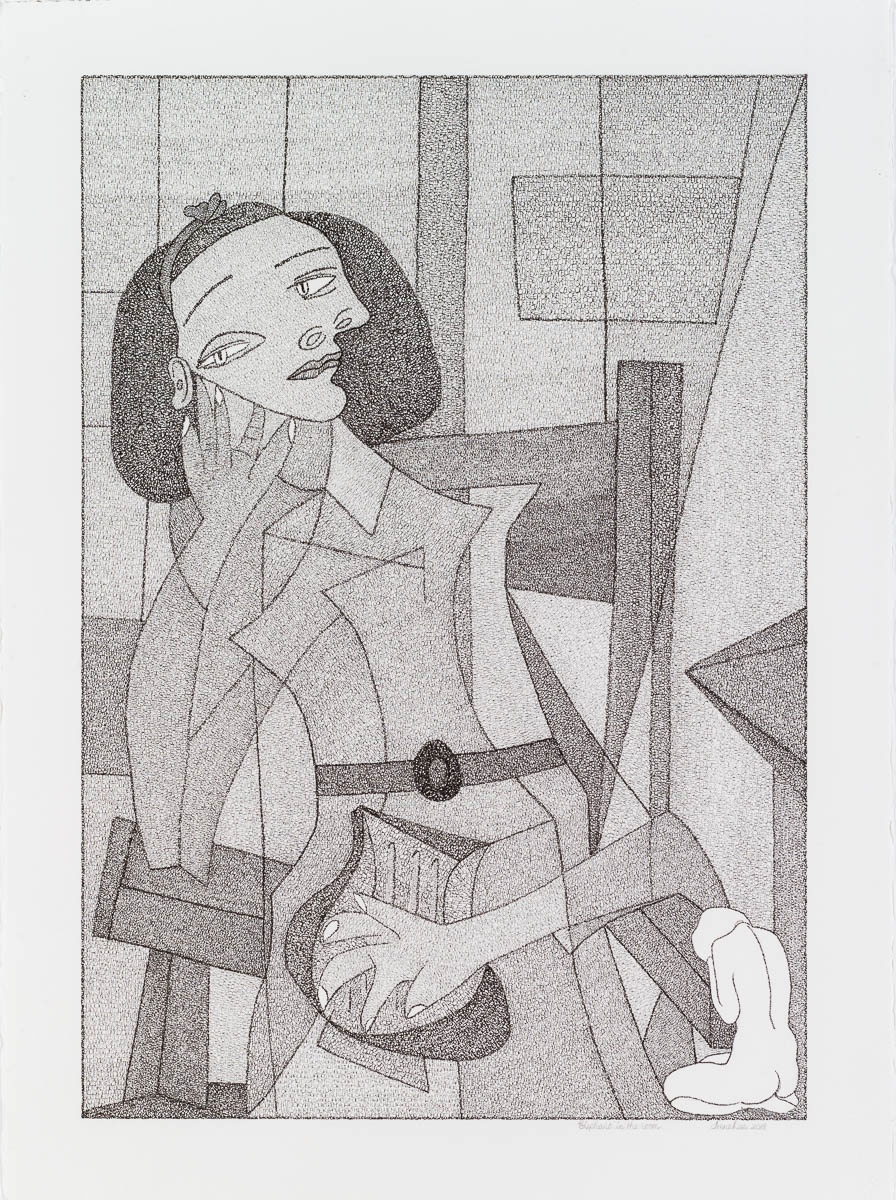

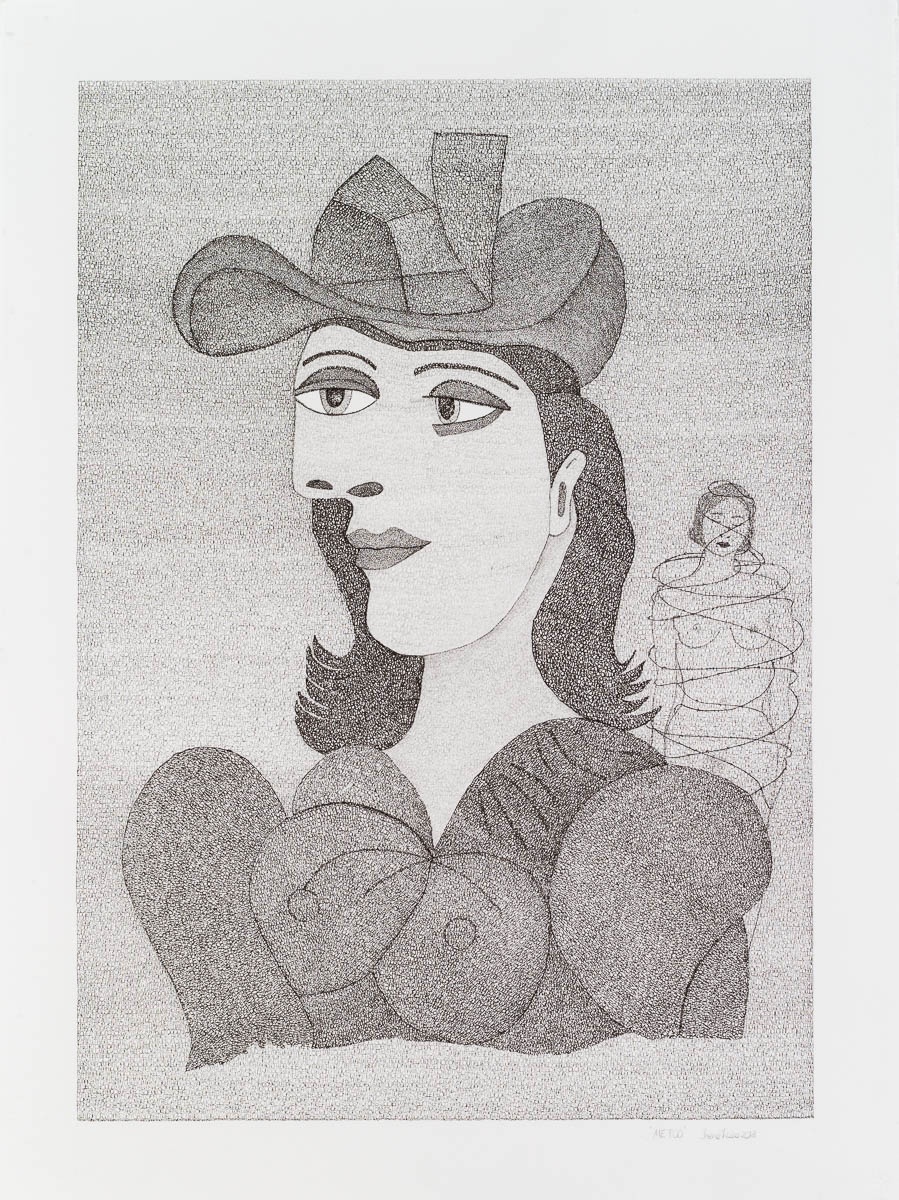

The Bell Jar images have been ripening slowly, but another new line of enquiry, into Picasso’s muses, has borne copious fruit. Having previously thought of the painter of Guernica as “a good socialist”, Lees’s eyes were opened by the discovery of his remark to Françoise Gilot: “For me there are only two kinds of women, goddesses and doormats”. The more she read about the artist’s models and mistresses, the more astonished she was at how he treated them “as one would any other commodity, like paint, crayons, an easel, food or clothing”, rendering them unrecognisable in images that merely screamed ‘Picasso’. In her new series of drawings in the master’s style, she sets out to avenge them. Picasso left later biographers to tell the stories of his women; by writing their stories into her images, Lees allows them to speak for themselves. She is not out to rewrite patriarchal history. “People say, take the monuments down. I say no: keep the monuments, but tell the story.” Even so, she marvels at how for more than four decades Picasso “just replaced one mistress with another. In a way, it was like Russian dolls, popping them one inside the other.”

Russian dolls are next on her creative agenda. For this incurably inquisitive artist one thing leads to another, in an unbroken line.

Laura Gascoigne

March 2019