In 2013 Lund Humphries published Gardiner’s monograph, The Art of Jeremy Gardiner, Unfolding Landscape. Wendy Baron, who first encountered Gardiner’s work in 1983 at the Royal College of Art postgraduate show when she acquired his work in her role as Director of the Government Art Collection, writes in the foreword that Gardiner and his work, while belonging to the strong and enduring tradition of English landscape painting, maintain a vision and sensibility that is unique; “The abstracted reliefs of Nicholson, the dance of transparent organic shapes of Tunnard, the metaphysical preoccupations of Nash, the ragged forms and scumbled surfaces of Lanyon, have informed and enriched, but never dictated, Gardiner’s personal language.”

In this exhibition we get to witness the development of that personal language in both prints and paintings made over twenty years, featuring places of great personal importance to Gardiner, including Dorset, Devon and Cornwall. Gardiner says “My work reflects a deep and long-term interest in the geology of landscape and how it is shaped by the forces of nature and by unfolding the landscape through my painting I am inviting the viewer to reflect on their own transient relationship with the physical world.”

Gardiner’s fascination with the Dorset coast started as a boy, when he regularly stayed with his grandmother in Swanage. Ian Collins writes in Unfolding Landscape “Surrounded by gentler and more gentrified counties, save for its embattled border with the sea, Dorset instantly presents itself as a place apart – even at the subtlest northern edges, mobile phone signals can thrillingly cease. We have enjoyed the most dramatic approach of all, crossing Poole Harbour on the chain ferry from Sandbanks to Studland, for an exploration on the Isle of Purbeck and the origins of Gardiner’s life-long fascination with Britain’s Jurassic Coast. Like a partly opened concertina, this craggy and shingly swathe of Dorset and East Devon shoreline folds and stretches for 95 scenic miles, with rocks forced up vertically by tremendous subterranean pressure and then cast into fantastic formations due to unequal resistance to the pounding of the sea.” He would explore the area on foot, bicycle and boat discovering the stretch of coast from Old Harry Rocks in Dorset to Orcombe point in Devon, see Golden Cap, Dorset, 2007 and Durdle Door and Ammonite, Dorset, 2007. This is a landscape that Gardiner has walked repeatedly and known in all seasons for over five decades. Swanage became pivotal to years of exploration. In 1992 Gardiner rented Number 2 The Parade, a first-floor flat on the sea front in Swanage occupied by Paul Nash in 1935 when he was writing his Shell guide to Dorset. The material gathered during these visits inspired the Ballard Point pictures, Ballard Point No.9, 1998 and Ballard Point No.11, 1998. These paintings evoke a sense of place as achieved by the landscape painting of Paul Nash and pay homage to Ben Nicholson with the impression of comfortingly familiar domestic objects in the foreground.

In these paintings we see how Gardiner builds up and constructs his paintings, not using drawing as his starting point, but a prepared wooden panel on which further wooden pieces are added and the development of the image takes place. Margaret Garlake in the 2000 catalogue that accompanied the Ballard Point series observes: “While Ballard Point is instantly recognisable in the upper part of each panel, about half way down is a densely worked and less easily deciphered still life. These are set within the wooden relief so that we see them as though through a window. Gardiner first constructs this notional window. Then he attaches the small wooden objects and finally he applies many layers of paint which he then scrapes down and overpaints so that the intermingled strata echo the multiplicity of memories that inform the work.”

The Cornish coast has become equally important to Gardiner. While the textural landscape style of the St Ives school artists Ben Nicholson, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham,

Peter Lanyon and John Wells are important influences, Gardiner’s view and style was expanded by the formalism of American art during his fourteen-year teaching career in the US. John Tunnard is a considerable influence both for his affinity with the Cornish coast and natural history, but also an artist with a shared interest in science and technology, both artists enjoying experimental and complex methods of working. Peter Davies in the monograph talks about “taking forward the essential achievements of the modernising St Ives landscape artists.....an analytical formalism drawn from diverse modern movements like cubism, constructivism and expressionism and in the case of Tunnard – surrealism”. The resulting work becomes a hybrid style as much informed by American formalism as by the pastoralism of the English ‘school’. See Atlantic Breakers, Porthtowan Coast, Cornwall, 2010. Charles Darwent aptly observes, “Jeremy Gardiner’s art recognises that modernity is cumulative, that newness is built upon oldness”. As Simon Martin notes in the monograph, “an artist’s ability to look instructively at the work of other artists and to enrich their own working practice without straying into the territory of the pastiche is testament to their strength of vision and spirit of enquiry”.

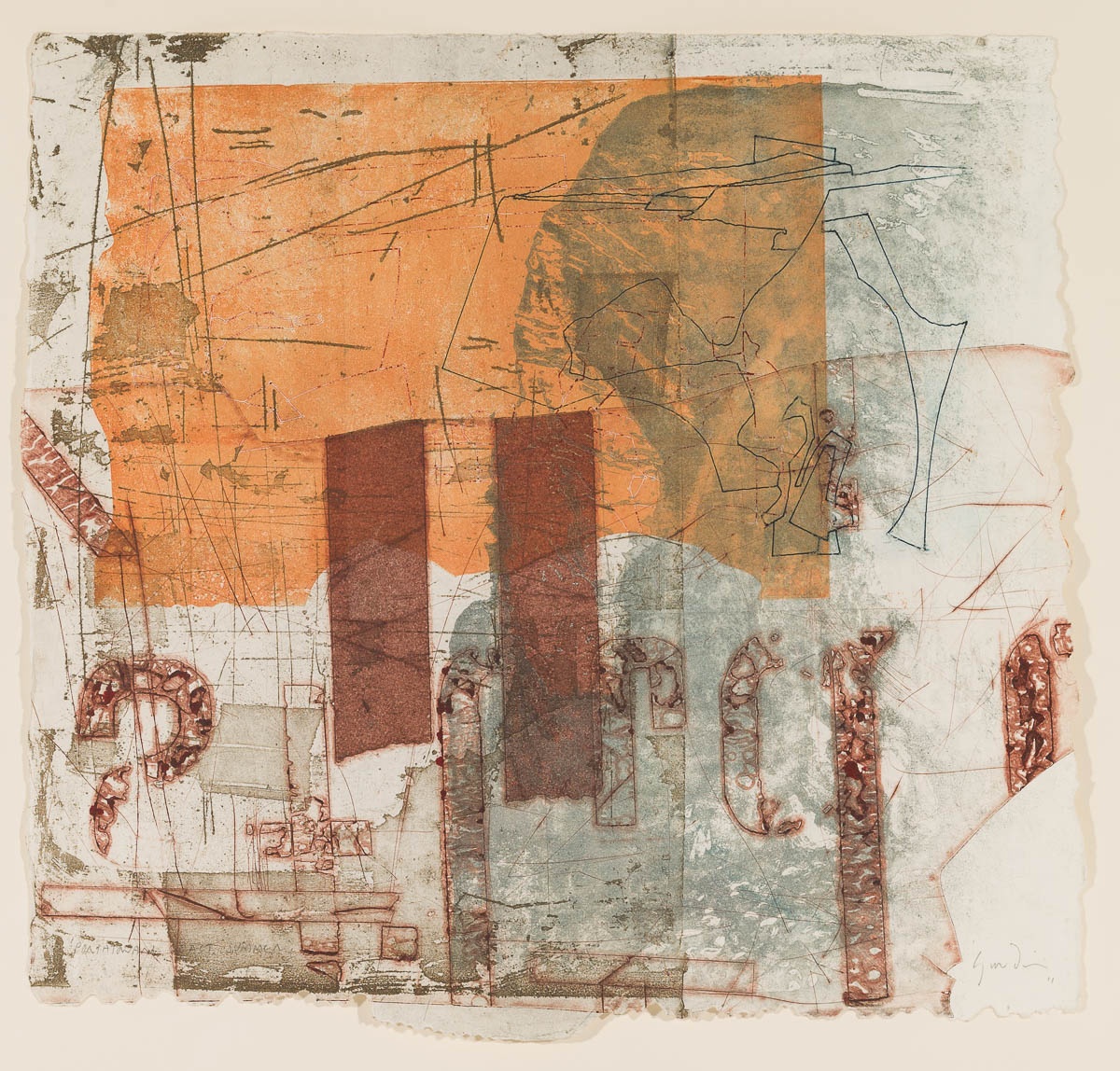

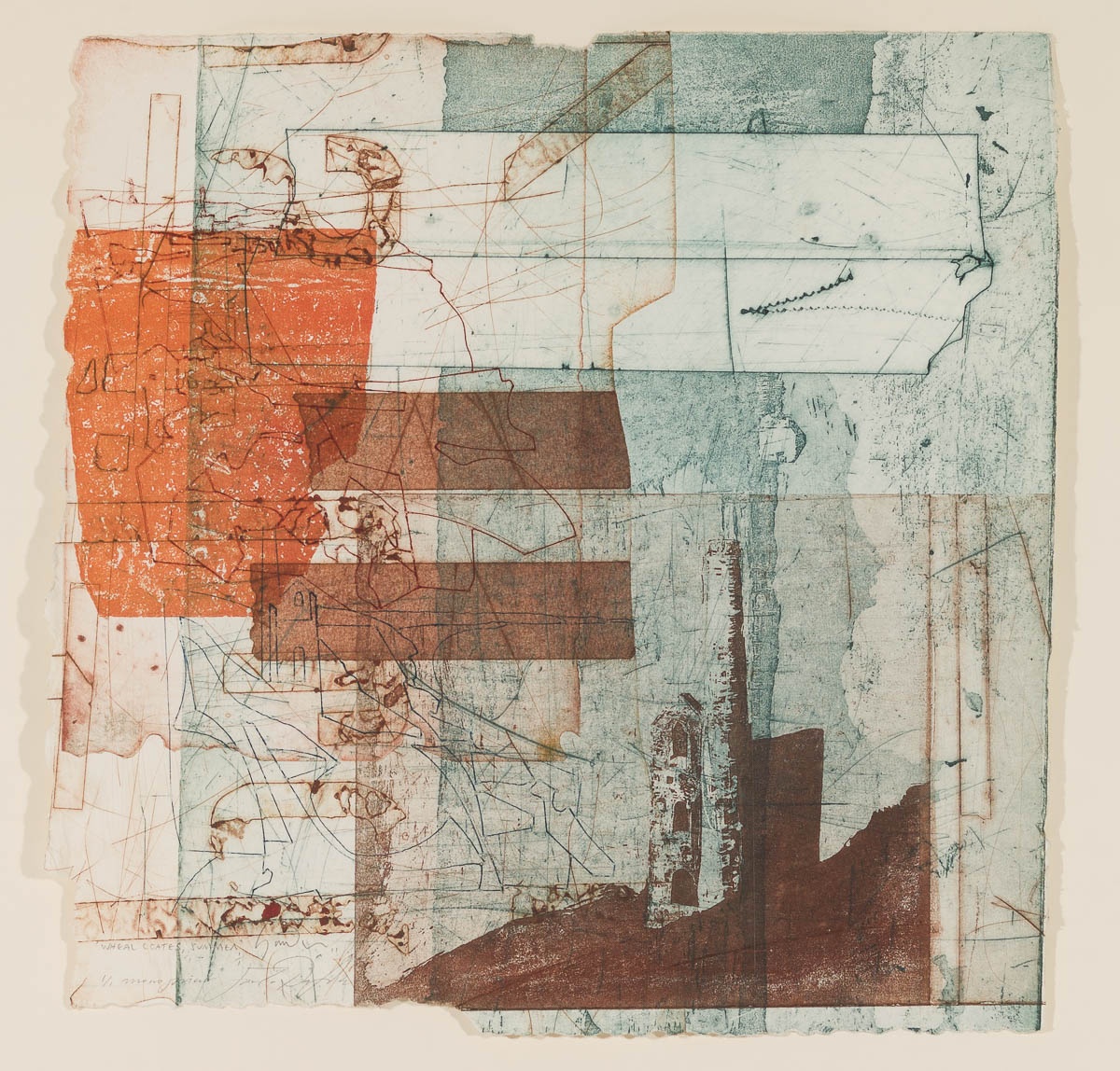

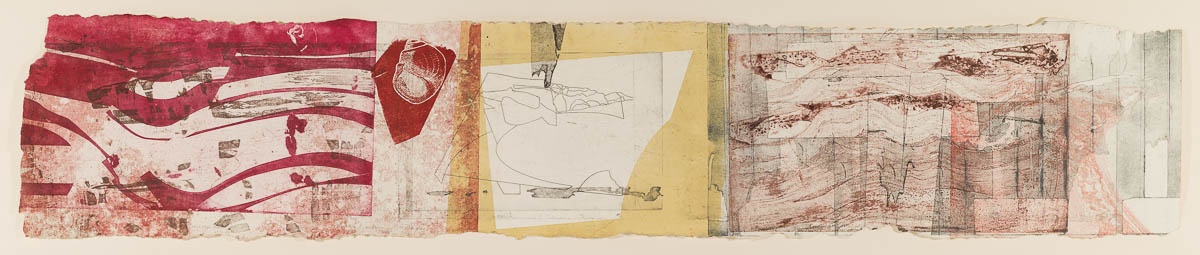

Gardiner has always enjoyed the challenge of technically complex prints. In 1992 Gardiner taught printmaking at his old college, the RCA. Once again in printmaking he crosses established boundaries between old and new forms of printmaking. Part of the importance of printmaking for Gardiner is the physical interaction with a surface on which he could employ industrial processes and equipment. The monoprints seen in this exhibition are predominantly intaglio monoprints, a painterly form of printmaking in which each impression is unique. These prints see a painstaking assemblage of elements, from coastal views to cross-sections of fossils to patterns that reference the land. One section might be a view of the Dorset landscape seen on a coastal walk, another a cross-section of a fossil found in that location, whilst another element might be the contour patterns seen from the air captured by LiDAR, an optical remote sensing technology that can measure the change in elevation of the landscape using pulses from a laser. Being the ambitious artist that he is Gardiner made these in both vertical and horizontal formats, see the variety of plates used in Seacombe, July, 2012 and Arish Mell, March, 2012.

2011 saw the first in what became a long study of lighthouses. In this exhibition we see one of the first of these studies in Sheer Cliffs, Pendeen Lighthouse, 2011, revisited in Daybreak, Pendeen Lighthouse, Cornwall, 2016. Christiana Payne in her 2016 essay for the Pillars of Light catalogue focuses on the importance of the lighthouse metaphorically as well as practically, describing them as “conquest of darkness by light”. Lighthouses by their very existence are nearly always located in dramatic positions on rocky exposed areas, often with big winds and big seas. This brings both challenges and opportunities in their visual interpretation. As Payne observes, “The lighthouses themselves are extremely useful compositional devices. A vertical accent against a predominantly horizontal landscape, a flash of white against the darker land, sea and sky, a mathematically regular, precise form against the amorphous qualities of rocks and hills.”

As we see in Daybreak, Pendeen Lighthouse, Cornwall, 2016 and Setting Sun, St Anthony’s Lighthouse, Cornwall, 2016; “Even when they are tiny forms, seen from a great distance, they draw the landscape together, gathering up the lines of perspective and structure in a single point of focus. Many artists have painted lighthouses, but few have been as successful as Jeremy Gardiner in communicating a sense of the uncompromising landscapes within which many of them sit.” Payne also suggests that by braving the elements in his plein-air practice Gardiner replicates, to an extent, the isolation and danger experienced by the keepers. In Turquoise Harbour, Lundy South Lighthouse, 2016 there is what Payne describes as “a dramatic tension between the regular lines of the lighthouse and the irregularity of its surroundings”. The loose impression of landscape contrasts to the precision of the ship at dock and the architecture of the building. Once again layers; layers of meaning, personal, scientific, historical and physical layers in both the place and the painting of it.

The two most recent works in the exhibition Mist at the Needles, 2017 and Shining Morning, St Ives, 2017 are watercolours. “The surfaces are embossed and entrenched, incised with precision drawing, the cliffs and coastlines, the buildings and streets are cut into the paper and creating the effect of a moulded surface or a sculpture in low relief. He is keen on the fruitful contrast between the built environment and the natural context, focusing on architecture but also on the movement of tides, the spring rhythms of rock and earth.” Andrew Lambirth.

So I turn back to Wendy Baron, to summarise this important body of work made over an extended period of time by an artist who will undoubtedly leave his mark on the British tradition of landscape painting and exploration; “Thus when the history of British art in the early twenty-first century comes to be written, Gardiner’s paintings will undoubtedly endure as objects not only of great beauty, but equally of penetrating insight.”

- Candida Stevens, Curator

Close up's from 'Setting Sun, St Anthony’s Lighthouse, Cornwall', 2016