Essays from the exhibition catalogue, by Charles Saumarez Smith, Candida Stevens and Paul Bonaventura

Foreword - Charles Saumarez Smith

I first met Stephen Farthing when I was Director of the National Portrait Gallery. I was, for obvious reasons, interested in artists who investigate and stretch the conventions of portraiture in an intelligent way. I became aware of the work Stephen had done in the 1970s playing with royal portraiture, as in his Louis XV, now in the Walker Art Gallery, in which he teased the viewer by breaking down the components of Hyancinthe Rigaud’s of official portrait of the young Louis XV and treating them with deliberate irony, an idea which he correctly now considers as part of an early interest in the classic strategies of post-modernism.

Knowing that Stephen was Ruskin Master of Drawing in Oxford, I thought that he would be well placed to undertake a commissioned portrait of the founders of the major social historical journal, Past and Present, many of whom were themselves associated with Oxford, including Sir John Elliott, Regius Professor of Modern History, Christopher Hill, who had been Master of Balliol, and Sir Keith Thomas, President of Corpus Christi. He undertook the commission with great vigour, documenting his conversations with each of the sitters, enjoying establishing the network of their original relationships, and producing a group portrait which I still very much admire – a cool and cerebral depiction of the post-war, mostly Marxist, intellectual establishment.

Since then, I have kept in touch with Stephen as he migrated to New York as Executive Director of the New York Academy of Art, back to London and to Chelsea School of Art as the Rootstein Hopkins Professor of Drawing, elected an RA in 1998, and now the very active chairman of the RA’s exhibitions committee, which gives him an important role in overseeing the institution’s exhibitions policy. He is unusual as an artist in being so sociable, enjoying the politics of college life when he was at Oxford and as happy to talk about, and write about, the practice of art as he is to practise it himself.

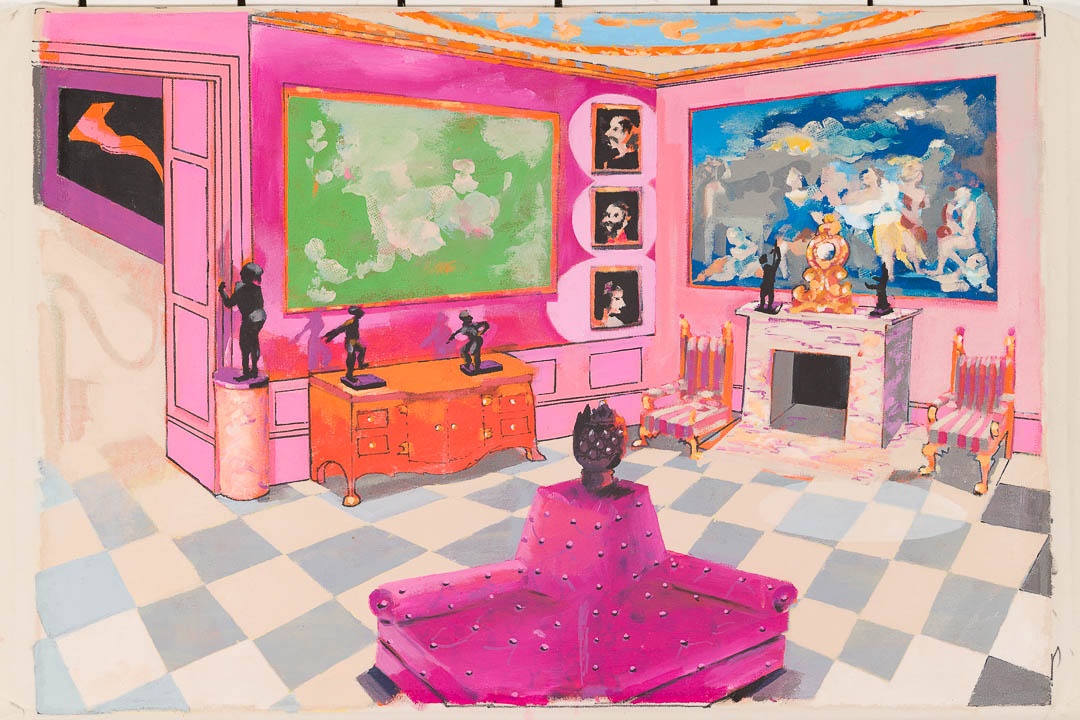

Now, in his exhibition Museums of the World, he is investigating the complex relationship between works of art and their setting – the way work is displayed and how the systems of display, including the lighting, the seating, and the display cabinets condition the way works of art are viewed. It includes a new version of a work which was shown in last summer’s annual Summer Exhibition, called Room 3, A Museum of Vernal Pleasure (2017). It is a depiction of Gallery 3 at the Royal Academy, the grandest of Sydney Smirke’s top-lit, 1868, beaux arts galleries, filled deliberately incongruously with versions of the work of currently well-known artists, including, most obviously, a large landscape by David Hockney and a pot by Grayson Perry. It is painted with Stephen’s particular brand of intelligent irony, faintly mocking the foibles of the art world, but with good will, not satire.

The other paintings in the series show a version of the Yale Center for British Art (but unimaginable with pink sofas), the magnificent clutter of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, 1, E 70th Street, the address of the Frick, and the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. They demonstrate Stephen’s worldliness, his ability to travel in the imagination, his knowledge of the conditions of art display, and the contrasts between the ways that art is displayed on different continents, in different milieux, in private and in public. Intelligent and knowing wit is not something which we normally look for in contemporary art, but it is evident in the work of Stephen Farthing.

Charles Saumarez Smith is Secretary and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy of Arts

A meeting of minds; artist and collector, art and collections - Candida Stevens

This extraordinary meeting of minds between artist Stephen Farthing RA and collector Simon Draper, also owner of Manor Place Museum, demonstrates the inextricable link between creation and collection. Each is a passionate pursuit, a form of creativity and expression that is practised with discipline, absorption and commitment. Both artist and collector hope to reveal and give meaning to their respective worlds and for me, from a curatorial perspective, the striking connection in the works created by Stephen and placement of his paintings in Simon’s museum, is an act that offers a most intriguing, insightful and genuinely immersive experience.

The idea of exhibiting part of this exhibition within a private collection was developed when Simon kindly volunteered Manor Place Museum, not far from our gallery, as a venue for a suitable exhibition. While working with Stephen on the production of his Museums of the World series, the association was obvious. His paintings study collecting and collections that guide us from the Cairo Museum, with its 4000 year old Ostrica drawings, to a recent assembling of works by contemporary artists at the Royal Academy Summer exhibition. The common references that exist between these two individuals have made for a fascinating dialogue about collecting, collections and their significance. Study at leisure the connections.

Art collecting existed in the earliest civilisations, Egypt, Babylonia, China and India. Precious objects were assembled in temples, tombs and palaces. Royalty were important in accumulating these ‘cabinets of curiosities’, almost anthropological assemblies of artefacts from travels. Collecting evolved into

its modern form during the Renaissance when it was associated with the patronage of the church, state and crown. By the 18th Century well-to-do homes were expected to contain fine objects from paintings to porcelain, hence a rise of collecting as a pastime. By the 20th Century individual collectors clearly represented a driving force within specific artistic markets and movements, whilst today it is increasingly common for collections to be built by corporations and institutions.

On a macro level, public collections have a profound role to play in the communication and preservation of culture and its values. On a micro level, individual collectors can also have influence, through demand for a style of work, perhaps a commission. Sometimes the two link and many historical, private collections have been the beginnings of several of the major museums we know today. Major examples where few or no additions have been made include the Wallace Collection in London and the Frick Collection in New York, both of which Stephen has included in this series, The Museum of the Boudoir: Manchester Square, London, and The Museum of Domestic Wealth: #One E 70th St respectively. The role of collector and collections is shifting again. In this time of globalisation and digital acquisition the way in which art can be seen, preserved and bought has evolved dramatically. The traditionally, Western influenced art market is opening out and new collectors have begun to emerge in South America, Asia and the Middle East, where some of the earliest known collections began. It will be interesting to see if international, eclectic collections will develop and respond to this moment – perhaps even provide a new age for museums. Yet, for all these changes over the centuries, the behaviour of collecting remains largely the same. Acquiring art still grounds us to something tangible by which we are moved. It remains a deeply human and enduring activity, inspired by creativity and intellectual curiosity, and offers us a physical exploration and connection to both our collective and personal histories.

It has been a great pleasure to be instrumental in bringing artist Stephen Farthing and collector Simon Draper together. I believe the role of a curator is to present and create new and different ways of looking at and experiencing visual art and to remind us of the deep impression it can have on our emotions and thoughts. This exhibition allows us to do that and I am grateful to both Stephen and Simon for being so open to the idea. I felt it fitting that a final piece in the series should be created by Stephen of Simon’s museum at Manor Place, The Museum of Post-Cubist Painting: Near Chichester. It comes from the dialogue between us all and is a pleasing edition to a body of work that will no doubt be meaningful for many.

Interestingly, there are a number of personal links between the paintings of the museums in this series and those who have been involved in the exhibition. Of course, for Stephen his link is to all the museums featured but perhaps mostly the Royal Academy, where he is an Academician and current Chairman of the Exhibition program. For Charles Saumarez Smith, to the Royal Academy, where he is Secretary and Chief Executive, as well as the National Gallery where he was previously Director. For Paul Bonaventura, it is the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology from when he was the Senior Research Fellow in Fine Art Studies

at the University of Oxford. For me, it is serendipitous that The Wallace Collection is included;

a collection that I was taken to visit aged 11, recalling the first time I became truly spellbound by visual art and moved by an associated journey into our history. We may each have just such a moment; I hope Stephen Farthing’s Museums of the World will remind you of that.

Les musées imaginaires - Paul Bonaventura

In museums things are anointed with a cloak of specialness. To some extent this aura comes from their designation as part of a collection, where each object is enriched by the company it keeps... Museum objects are distinguished by multiple layers of histories... [and their power] also rests in the fact that they are pregnant with potentially new information and new insights. So while museums keep things as physically unchanged as possible, they also invest a lot of energy into augmenting their meaning.

Ken Arnold, A House for the Curious

A couple of years ago the Picturehouse cinema chain screened a short documentary called See everything in which the American lmmaker Alex Gorosh attempted to see every piece of art in London in one day. The film was commissioned to promote the Art Fund’s National Art Pass and showed Gorosh sprinting through the capital’s museums and galleries on what was clearly a mission impossible – a race against the clock with only one outcome. Bagging more than 140,000 pieces across thirteen locations, from the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the east to the Victoria and Albert Museum in the west, Gorosh certainly has claims to being a record-breaker when it comes to seeing the most art in a day. Yet London’s museums and galleries allegedly contain more than 20 million items so he racked up less than 1% of the total.

The climax of his art-driven marathon finds Gorosh at the National Gallery. Realising that he has nowhere else to be he finally slows his pace and starts looking at the collection more closely, halting in front of Georges Seurat’s luminous Bathers at Asnières. At which point he reaches for the consolation of philosophy and alights on an observation by high-school slacker Ferris Bueller: ‘Life moves pretty fast and if you don’t stop to look around once in a while you could miss it.’

To my way of thinking there is a little of See everything in Museums of the World, Stephen Farthing’s newest group of paintings. While implicitly acknowledging the hopelessness of their respective ambitions – see everything locally, go everywhere globally – the filmmaker and artist are locked together

in an obsessive relationship with the temples of art. Moreover, in their restless quest to update their lists both men owe something, at least, to Jules Verne’s classic escapade Around the World in Eighty Days.

Verne’s peripatetic novel was published in 1872 and marked the end of the age of exploration and the start of the age of global tourism. During the course of the 19th century technological innovations in rail and sea transport opened up the possibility of rapid, affordable travel such that anyone could now sit down, draw up a schedule and embark on a journey of personal discovery. Three thousand years after Homer’s seminal tale of a voyage interrupted, Around the World in Eighty Days crystallised the concept of time as theme in the modern world.

While Museums of the World is self-evidently about place and space, it too is about time. Not just the time it took Stephen to identify and visit the institutions that figure in the paintings, but also the time he invested in imaginatively reconfiguring their structure and contents. Plus the time it takes us as viewers to pick them apart. Rich in detail, the Museums don’t work if we have any form of attention deficit. As Stephen says, you’ve got to lose yourself in them just as you lose yourself gazing into a crackling log fire. On a visit to his London studio last summer, Stephen explained to me that all the canvases in the series were painted over the past two years in Mexico City, where he found himself living with his wife and family. Some of them connect with the much larger museum paintings that he was making in New York City from just after he moved there at the turn of the millennium, but the rest have no backstory and simply relate to what he is looking at and thinking about now.

Stephen wanted his new Museums to be small partly for practical reasons – the difficulty of selling large pictures, of not having a big studio, of frequently being on the move – and partly because he felt like painting sitting down. In playful riff on Henri Matisse’s declaration that he wanted his art to be a calming influence on the mind, ‘like a good armchair’, Stephen has turned his vocation into a sedentary activity.

‘These days’, he admits, ‘I paint in what is effectively a library. There are books all around the easel and I sit in an armchair to paint. I maybe have three canvases on the go, but I do one painting at a time and turn the rest to the wall... It’s less about making in a studio and more like writing a letter, but I can’t write straight off. I have to self-edit on the computer all the way through because writing doesn’t come easily to me. I’m nearly always engaged in a process of refining a piece of writing and it’s the same with my painting. I’ve come to enjoy the actual mechanics of building a picture and not doing it in the workshop atmosphere of a traditional studio.’

The fifteen pictures that currently make up Museums of the World were cut from their original supports for shipment to London and re-stretched on larger supports because Stephen didn’t want the paint to reach the edge of the canvas. ‘It’s such hard work not painting to the edge,’ he confesses. ‘It requires a kind of restraint that doesn’t come naturally to me. I’ve always painted to the edge in the past so this is a new conceit.’

Stephen regards his Museums as maquettes or models. When the occasion arises – through a commission, for example – he can paint one on a much grander scale and then he doesn’t worry so much about the edges. The one big painting that has already come out of the series is Room 3, A Museum of Vernal Pleasure, which is a re-working of The Museum of Vernal Entertainment: London. Stephen painted the larger of the two canvases for Room 3 of last year’s Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts and it features on the front cover of the catalogue for the show. ‘In both paintings,’ he confirms, ‘I’ve got a back view of a Michael Sandle sculpture and I’ve played it off against a David Hockney on the right and a Rose Wylie to the left. And I’ve turned the Zaha Hadid architectural model into a massive sculpture. Likewise the Grayson Perry pot. In the distance there’s a painting by Paul Huxley and a painting of mine.’

By including his own work in the two pictures, Stephen expresses a sense of belonging – to the Royal Academy of Arts, to the world of contemporary British art – and this sense of belonging pervades all the Museums. Stephen is the guide by which we enter these institutions. Making a pattern out of a muddle, we

see their collections and exhibitions through his eyes and the works that he has chosen to depict constitute a striking canon of achievement.

Many of the preoccupations that surface in the Museums were flagged up in two of Stephen’s earlier travelogues, which were given over to fanciful portrayals of major cities from around the world. Like The Knowledge and Falsifying the Log, the Museums represent two kinds of journey – one geographic, the other artistic – and we can trace the provenance of some of his techniques right back to his room-based paintings of the early 1980s, such as Mrs G’s Chair and The Nightwatch.

‘Over the decades I have got better at painting,’ Stephen says. ‘I don’t necessarily make better paintings, but I’ve got better at the craft of painting and I’m more inclined to take risks. I think this body of work is less manufactured than some of my earlier paintings in that I’ve taken more late risks with them rather than the risk being at the beginning of the process. I’ve tended to start with a tight little subject and then wrecked it later on... I enjoy mixing up colours and sticking them on. It’s physical pleasure and when you get that right that experience transfers to the viewer and they get physical pleasure too.’

In the Museums anything that looks like artistic bravado has been manufactu- red and there is always some kind of diversion from the art on display. ‘The gallery is about showing art,’ he says, ‘but what I’m also showing is a distraction in the gallery. So around the frame of the window in the Whitney, for example, I’ve used a fluid medium to depict dampness or rot as a way of bridging the space between the depicted artwork, the wall and the floor. It’s a softening device.’ The licence that Stephen has allowed himself in his Museums – the modi ed gallery plans, the repositioned artworks – carries over into the titles.

Cheekily irreverent, the titles reformulate the mission of the institution. Thus the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York morphs into The Museum of a Slice of America: Madison Ave, the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City becomes The Museum of Precolonial Imagination: Chapultapec, the Wallace Collection in London turns into The Museum of the Boudoir: Manchester Square, London and so on.

Stephen traces the idea of re-titling his paintings to a 2016 visit to the Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart. Described by its gambler founder as a subversive, adult Disneyland, MONA presents antiquities, modern and contemporary art from the David Walsh collection. Stephen sees the building, which is largely underground, as an Aladdin’s cave of cultural treats, but says there is no clear logic to the display – hence The Museum of the Each-Way Bet: Hobart.

While I sip my way through a second cup of coffee, Stephen shows me the finished canvases that will go into the exhibition with Candida Stevens Gallery. I’m particularly struck by his interpretation of Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware in The Museum of the American World View of Global Visual Culture: Manhattan. Stephen has previously made several copies of Leutze’s masterpiece in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but in this instance elements of the highly ornate frame have been given an opportunity to float free and they dominate the space of the painting. ‘Every now and then,’ he affirms, ‘your mind wanders in galleries and you let the pictures take you over.’

Around the time that Alex Gorosh was roaming the halls of the National Gallery, camera in hand, Stephen was putting the finishing touches to The Museum of Good Painting and Good Frames: Trafalgar Square. I think the two Vermeers on the back wall are terrific and Stephen is particularly pleased with his rendition of The Fighting Temeraire that does a great job of capturing J.M.W. Turner’s swirling brushwork. He’s also managed to transform George Stubbs’s iconic portrait of a rearing Whistlejacket into a jaunty pub sign.

Stubbs crops up again in the Yale Center for British Art a.k.a. The Museum of Art From A Small Island: New Haven. ‘I painted Stubbs’s Zebra first,’ he says, ‘and then drew a rectangle around it, which became the frame, and then drew another rectangle around it, which became the wall. And then I put in the grey floor and the light source. After which I painted the pictures in the background and finally the ectoplasm. Like the painting around the window in the Whitney picture, this loose handling is a way of me getting some of the energy out of the depicted painting and onto the depicted floor. It’s an attempt to give the zebra somewhere to go if it ever decided to jump out of its frame.’

As Stephen pulls out painting after painting I suggest that the maquettes add up to an index of nearly all the museums and galleries that he has visited over the past twenty years – the venues that have had the biggest impact on his thinking and development as an artist – and Stephen agrees: ‘The underpinning

principle goes as follows. You arrive as a stranger in a foreign city and you are looking at a way to relate to it. The museums and galleries are the places that I naturally gravitate towards, feel comfortable in, and want to spend time in. You can just sit there and look at the people and the art and try and work out how you’re going to fit in. In very practical terms it’s a way of me trying to integrate myself into a new environment.’

Being the trailing spouse of a US diplomat, and before that a regular fixture on the British Council exhibition circuit, Stephen is more travelled than most and is very much at home around world culture. It doesn’t always transpire that travel broadens the mind, but in Stephen’s case it does. Indeed, there is something surprisingly uplifting about his ritualistic acquisition of the world’s museums in paint. Although the process represents an act of possession, that ownership speaks of a deep-seated love affair and a profound and benign enchantment with artists and artworks from other times and other places.