-

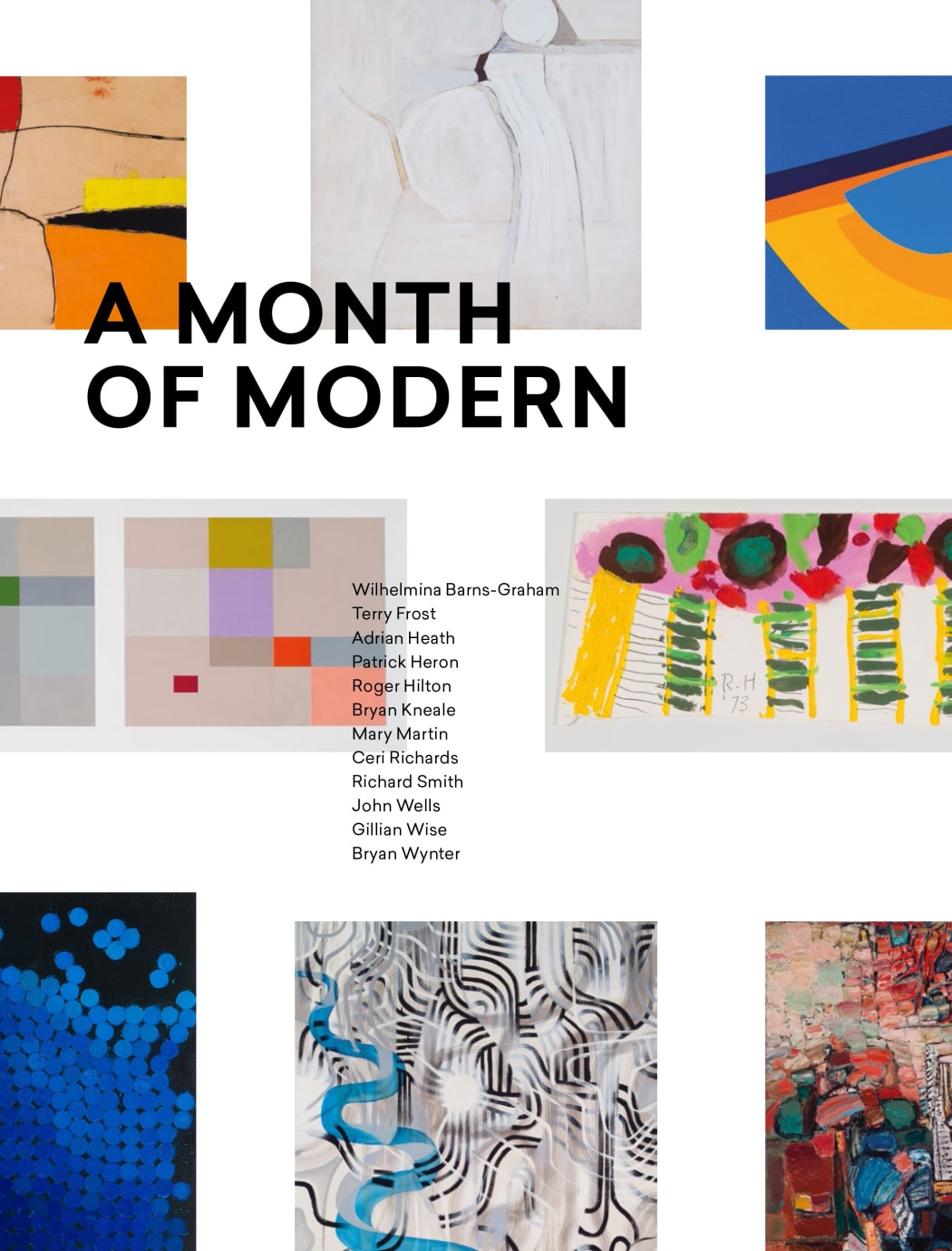

Why is textile art a trending art form today?

by Candida Stevens, Guest Curator of Threading Forms at London Art Fair 2020Textile art is having its moment, and it is a global phenomena. As the traditional ‘art-or-craft’ barriers are upended by artists and collectors alike, textile art, (often termed fibre art in the USA where artists in the 1960s and 70s were hugely influential in driving it's acceptance) which can include weaving, crochet, loose thread, carpets, hand and machine stitch and more, is at the forefront of ‘What to Collect Now’. Establishments within architecture, fashion, design and contemporary art continue to take note and comment on the advancement of textile art, it's increasing prevelance in major exhibitions and museums since the 1960s and its particular prominence in the past five years.

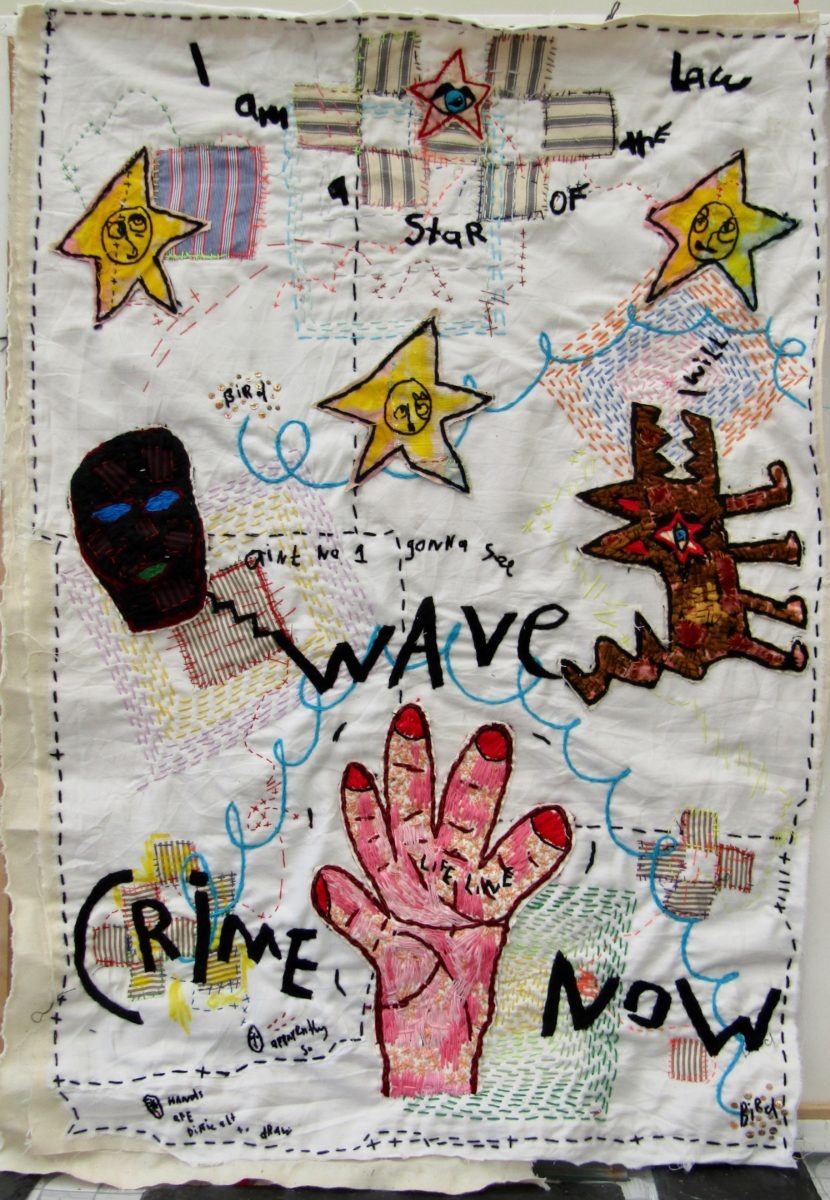

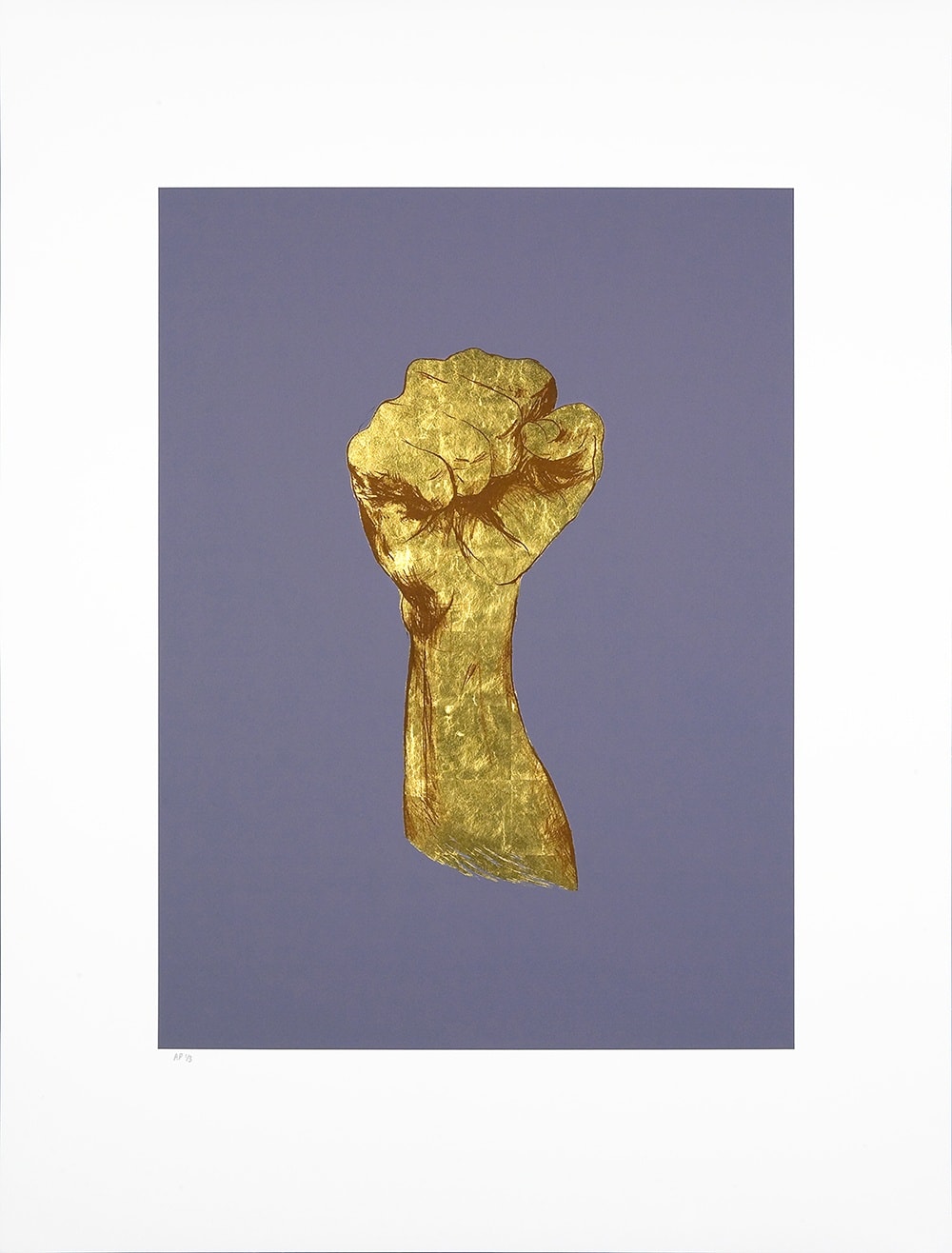

Hands are hard to draw, 2018 by Anthony Stevens

It is not the first time in human history that textile art has been highly sought after, but it has a turbulent history of acceptance and denial. While it has existed for millennia, it has not always been held in such high esteem by the art establishment. Positioning it within a quick potted history helps to understand.

'Fine Lines' by Jacy Wall, 2019

Woven tapestry, wool, linen on cotton warpAnthropologists estimate that people have been creating and decorating textiles, initially clothes and carpets for warmth, for 100,000-500,000 years. From these humble beginnings where plant and animal fibres would have been spun or twisted together to make functional objects, the journey becomes aligned with our political history.

The 14th-17th centuries in Europe saw wealthy patrons commissioning tapestries, a time when tapestry was often the costliest and most prestigious item in Medieval or Renaissance homes. Medieval English embroidery known as Opus Anglicanum was prized around the world for its skill and artistry. Made by both women and men, it signified the pinnacle of luxury in Medieval Europe. Simultaneously, in the Middle East they made beautifully crafted rugs using symbols and complex designs.

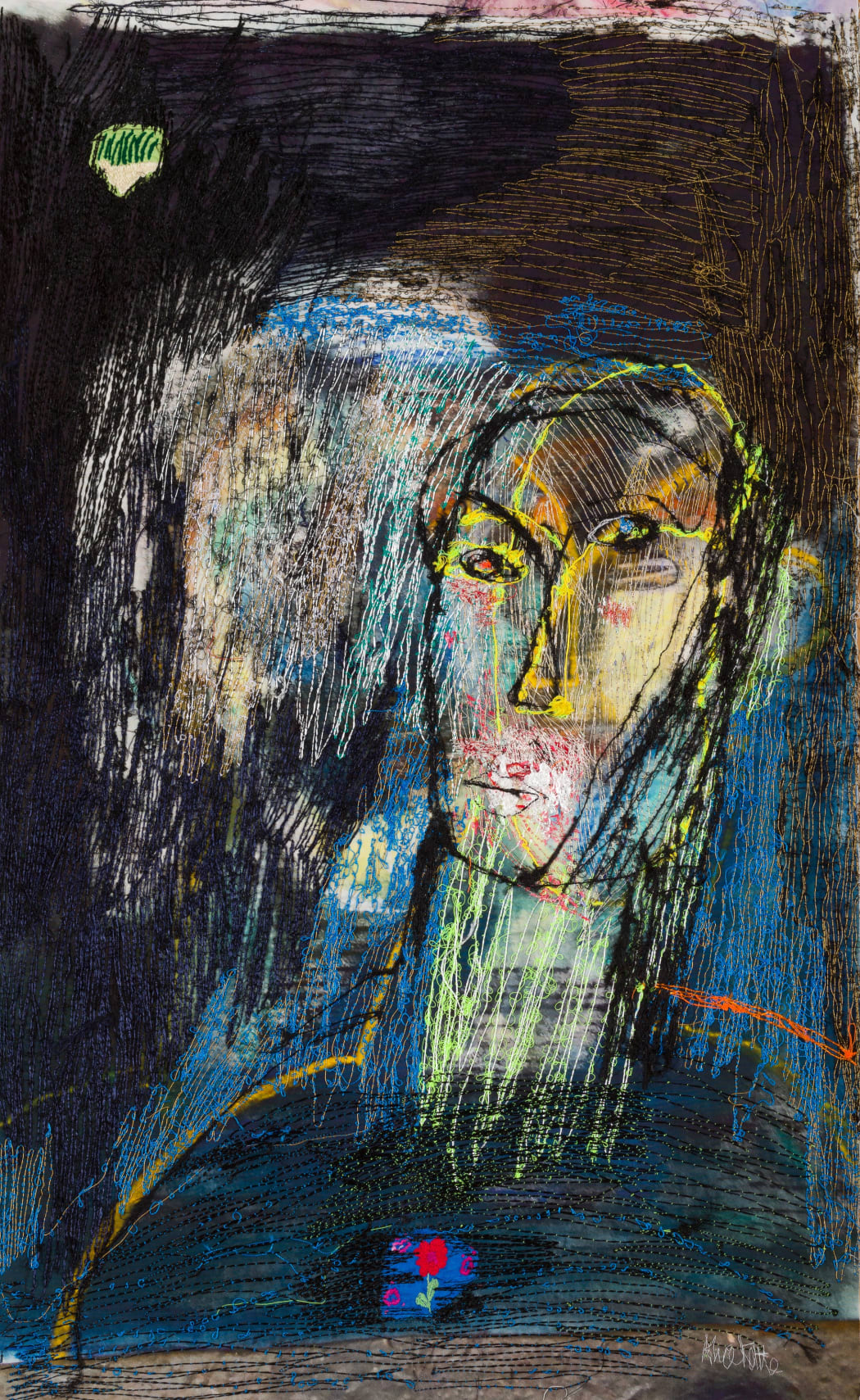

Beneath the Tree, 2019 by Alice Kettle

The Industrial Revolution (1760-1820) and associated burgeoning of affordable fabrics and machine production saw a plethora of textiles as functional objects. Stitching remained associated with the manual work of mainly women. During this period, in 1768, the Royal Academy of Art, London was founded. Eighteen months later it ruled that needlework was not permitted to be shown in the Academy, a damning indictment that textiles were not at the time regarded as high art, undeniably consolidating the prejudice and gender politics of this judgement. During this period of history, textile art fell from favour.

The years following the Second World War saw textile art start to meet its aesthetic and political potential. Used for political purposes and as a means of communication and expression, artists started to work with textiles in ways never previously seen. Visionary creatives moved beyond weaving, and began knotting, twining, plaiting, coiling, pleating, lashing, and interlacing and started exploring the 3D potential of textiles. Textile art started to enter the domain of scholarly writings and academia. By incorporating emotion, message and meaning into the work, artists elevated the status of their work – it had become high art once again. It was a time when the quality of idea and execution was what mattered, not the fabric used. Textile art is a powerful tool for communication which defies boundaries, this has contributed to the democratisation within the art and craft revolution.

The Challenge, 2017, handwoven tapestry by Caron Penney

Championed by women artists in the first half of the 20th century, with two important figures being Annie Albers and Sheila Hicks, textile art is territory now occupied by both men and women, leading to the emergence of some contemporary names including El Anatsui, Chris Offili and Damien Hirst. Prominent names who have become specialists in textile art include Alice Kettle (UK), Anne Wilson (USA) and Hiroyuki Shindo (Japan). Textile art has been surging in popularity with both collectors and artists since the 1960s. An important global event was the Tapestry Biennale in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1962. Today, new younger artists are interested in process, expression and experimentation, and the choice of material is of little significance, they are not confined by outmoded prejudice. Contemporary artists are pushing the medium to its limits. Artists are pushing the boundaries of what is textile and how textiles can be art.

So why is textile art trending now? Its earlier suppression allows it to be new, and therefore exciting. As it has been marginalised historically, it now has a chance to be seen as current and original. There is not a recent abundance of textile art, and with the time it takes to produce, neither is there an oversupply. This form of artistic expression allows designers, architects and artists to incorporate textile art in the spaces of today in unprecedented ways. Textile art is now hung in homes with fine art collections, and museums are acquiring major textile works for their permanent collections. For example, Southampton City Art Gallery, the Museum Partner of London Art Fair 2020, have recently acquired Odyssey, a seminal work by Alice Kettle. Kettle is one of a number of artists showing as part of Threading Forms, a curated section at London Art Fair 2020 attempting to bring to the fore a selection of galleries and artists who are both embracing the potential, and challenging the limitations, of thread in contemporary art. The section of the Fair aims to capture the breadth of different artists working in textiles and the growing appreciation of the medium as a beautiful and collectible art form.

But there is another reason why textile art is coming into its own. In a time of high consumerism and production, with the immediacy of digital, the painstaking handmade object has become a luxury. As millennials demand experiences not things, they can savour the experience of feeling a textile object and contemplate its creation. Textiles are part of all of our lives; we all experience textiles every day, they are familiar and essential. The time taken to stitch or weave is a comforting counterbalance to our rushed lives, soothing our frenzied minds.

About the author;

Candida Stevens is the founding director of Candida Stevens Gallery, a curation-led gallery established in 2014. Threading Forms is showing as part of London Art Fair on 22 – 26 January 2020 (VIP Preview 21 January). https://www.londonartfair.co.uk/

Arusha Gallery show work by Julie Airey

Atelier WeftFaced show work by Caron Penney and Katharine Swailes

Candida Stevens Gallery show work by Alice Kettle

Cavaliero Finn show work by Jacy Wall alongside ceramics by Björk Haraldsdóttir

Oxford Ceramics Gallery show work by Peter Collingwood

OutsideIn show work by Anthony Stevens

West Dean College weave on site throughout the fair

OutsideIn shows the work of Anthony Stevens

West Dean Tapestry Studio will be on site demonstrating weaving all week

-

Woman Thinking, 2019

Woman Thinking, 2019Within Each Other, Portraits of Ourselves

by Alice Kettle

Textiles offer a powerful medium through which to explore themes of cultural heritage, journeys and displacement. This exploration was central to Alice Kettle’s ambitious Thread Bearing Witness project shown at The Whitworth, Manchester in 2018. Through this project Kettle connected communities and individuals across the UK with the making of three monumental works inspired by the strength, resilience, and hospitality of refugees and asylum seekers. This new project Within Each Other, Portraits of Ourselves, launched as part of Threading Forms curated by Candida Stevens for the London Art Fair, sees Alice extending her reach beyond the UK, to incorporate communities around the world.

-

“We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice.”

John Berger, Ways of Seeing

Featured artists;

Helen Blake

Rob Lyon

Grace O’Connor

Anne Rothenstein

Dan Stevens

Perception is defined as ‘the way in which something is regarded, understood, or interpreted’. I hope that this exhibition will make us aware of how hard it is to see, how much perception plays a part, and that ‘seeing’ requires attention.

-

Irene Lees, Below The Surface

PRIVATE VIEW, SATURDAY 13 APRIL, 2-4PM. 13 APRIL - 11 MAY 2019

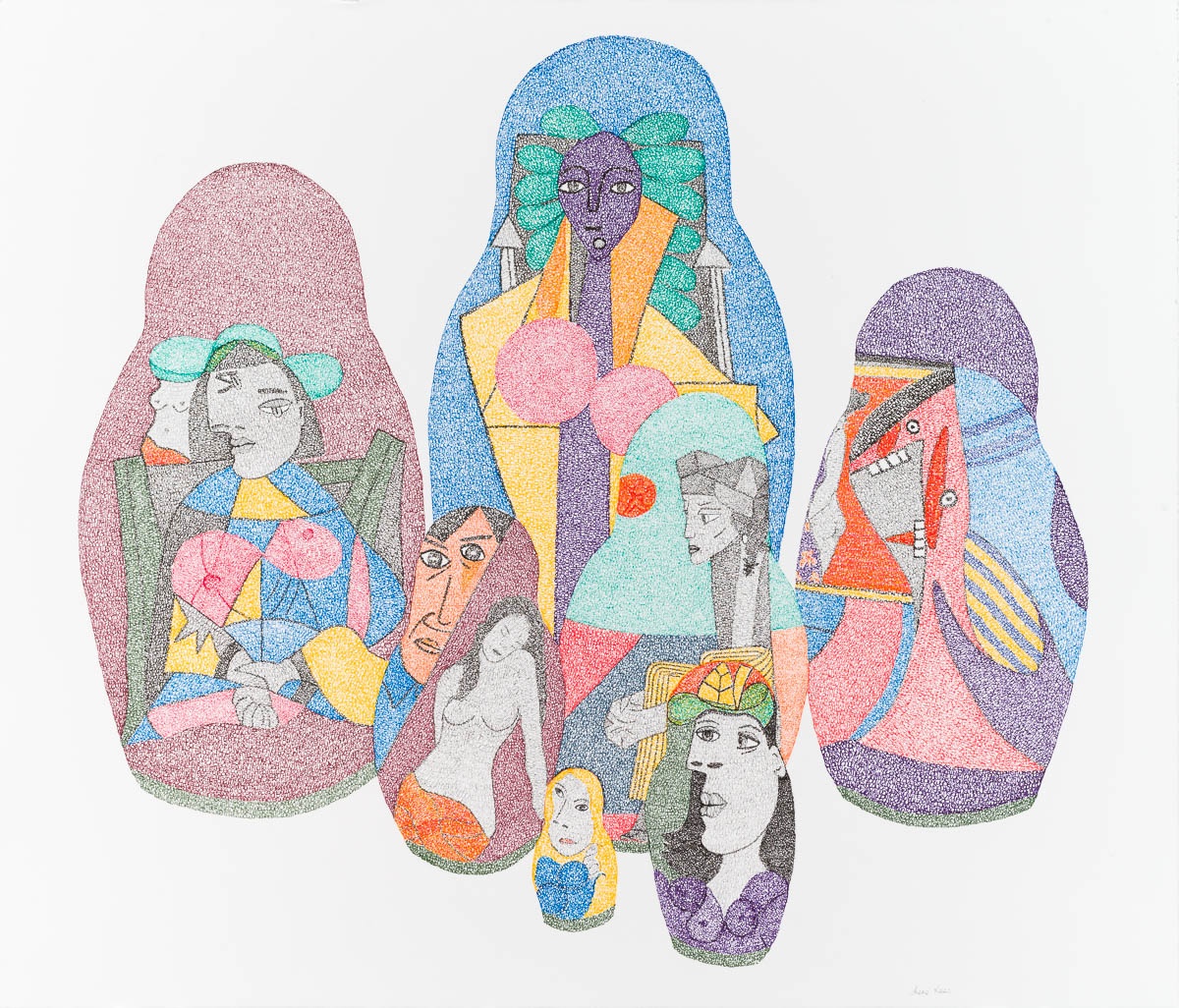

Below The Surface is a much anticipated solo exhibition of drawings by British artist Irene Lees. Produced between 2011-2019 the show brings together two new bodies of work, inspired by both Pablo Picasso and Sylvia Plath, alongside selected drawings from the past decade.

Irene Lees’ ever-questioning mind, her curiosity for human psychology, social history and injustice, is the driving force behind her work. Contained in these tightly conceived and intricately constructed drawings, is a strongly felt human emotion and spirit that filters through.

Through meticulous skill, research and application, she creates what she describes as her ‘artwork essays’; Hand-drawn rhythmic loops or layers of text, in an almost digital like rendering, which tell the stories of her chosen subjects. Writer and critic, Laura Gascoigne, introduces the catalogue for Below The Surface, writing; “Where [Lees] senses social injustice, she will pick up a thread and follow it to the source of the trouble, like Theseus tracking the Minotaur through the maze. Her drawings are a record of these journeys, charged with the emotions felt en route. In contemporary conceptual art research can easily be uncoupled from visual imagination, but Lees’ work is a perfect fusion of the two as she literally weaves the research into the image. Her work is conceptual in the true sense of the word: ‘Every time I’m doing something, it has to have a meaning.’”

Injustices borne by women are a constant concern for this female artist, which we see in four of the five series; the Picasso series, the Boko Haram series, the History of Body Packaging and the Votes for women. Here we demonstrate in more detail the motivation behind the two new series.

-

Celia Cook, Route

9 MARCH - 6 APRIL 2019

Read the insightful essay introduction to Celia Cook's current solo show ROUTE, written by creative producer and curator Georgia Attlesey.

-

Peter Waldron & Will Nash

PRIVATE VIEW, SATURDAY 2 FEBRUARY, 2-4PM, WITH AN 'IN CONVERSATION' WITH BOTH ARTISTS AT 2:30PM

Our next exhibition brings together two artists informed by mathematical reasoning, form, and the shape of things. Formal geometry rubs shoulders with the suggestion of humanity.

Both artists say they want the work to 'feel real' and for people to connect with the pieces intuitively. They both refer to themselves as makers.

The two artists, sculptor Will Nash and painter Peter Waldron, will be in conversation at the gallery this coming Saturday 2nd February at the opening of the exhibtion.

-

Touch

JULIAN BROWN, CELIA COOK, JANE HARRIS AND MALI MORRIS RA

Aristotle observed that 'Every body that has a soul in it must, as we have said, be capable of touch' and that it was only this sense that a conscious creature must have in order to 'be'.

An engaging and indepth essay, written by Professor Brandon Taylor, on the role of 'touch' as the foundation for what, and how, we see. Explored through four artists brought together for this exhibition; Julian Brown, Celia Cook, Jane Harris, Mali Morris.

-

We are delighted to be presenting a survey of prints and paintings that spans a 20 year period of Jeremy Gardiner’s career. It has been eight years since Gardiner’s exhibition A Panoramic View at Pallant House Gallery. While he embarks on a study of the Sussex coast for the first time it seems timely to welcome him back to Chichester and have the opportunity to share his journey so far. Many of these paintings have been held back for Gardiner’s personal collection, so we are honoured to be able to show some important pieces from these significant phases of his work. Gardiner has had an illustrious career, with work in numerous important British Collections and Museums. A number of essays have been written, over the years, by art critics and art historians alike. In order to summarise, without diminishing, the importance of the bodies of work represented here, we look back at what some of these writers have observed.

-

TRY ART OUT

A service designed to help you identify the art you want to live withTRY ART OUT

(Olivia Stanton, Almuth Tebbenhoff and Jonathan Huxley)Try Art Out is designed to help our customers identify and try out art that suits them.

We know that finding the right art can take time and that it is a very personal decision. It is important to feel confident of your choice, so we offer the chance to explore, experiment and try art out for yourself.

If you are looking for art, an exploratory conversation with Candida will guide

you through a variety of work to deduce the type of art that appeals. This can be carried out at the gallery or at your home. Her knowledge, understanding and insight will help form the basis of a specially curated selection for you to consider. Chosen pieces can then be trialled at home* to be contemplated further before purchase, or returned without obligation.Alternatively, if you already know what you like, you are welcome to request to view work to suit your requirements. The final pieces can then be privately viewed in the gallery or delivered to your home* for trial.

Once you have chosen your art work, we are able to advise on and organise framing and installation.

Get in touch to book a complimentary hour of consultation.

*All works selected to trial at home are done so on approval and without obligation. Large works or long distances may incur a courier fee.

"Being desirous of purchasing some examples of contemporary British art, but uncertain how to set about it, a chance recommendation led me to this excellent gallery. I have been a regular visitor to the gallery and have been introduced to the work of a number of contemporary British artists by the proprietors, Candida and Dan Stevens. I have been impressed by their willingness to spend time discussing the various artists’ work in the gallery with me, and generally offering helpful advice. Moreover, they are happy to consider visiting would-be purchasers’ homes and advising on suitable purchases. In addition, they positively encourage clients to try out paintings in their homes. They will also advise on the suitability of a particular painting for a particular room, and where to hang it in that room. Personally, I have found that kind of advice invaluable. All in all, this is a remarkably complete service, and I have been extremely pleased. Perhaps most importantly, my own dealings with the gallery have given me confidence that the quality of the art on display there can be relied on. Anyone wishing to purchase contemporary British art, particularly newcomers to the field, should consider visiting this gallery."

Stephen Bishop – Chichester

Artwork by (top) Nicola Green, Emily Ball

(Bottom left) Hen Coleman (Bottom right) Alice Kettle

Candida Stevens Gallery is a curation led gallery, established in 2014. It has quickly become an influential and recognised space for contemporary British art. Based on the south coast, and a regular participator at important art fairs, it shows an ambitious programme of exhibitions as well as new or relevant work by some of the finest contemporary artists working in Britain today. This includes, among others, pioneering textile artist Alice Kettle, influencers Eileen Cooper RA OBE and David Nash RA OBE, artist-educators Stephen Farthing RA and Katie Sollohub, technically excellent Hen Coleman and Jeremy Gardiner as well as politically engaged artists Irene Lees and Nicola Green.

With an energetic, curatorial curiosity Candida has gained a reputation for her integrity, eye and approachable manner. “Candida participated in our Executive Masterclass programme on Art Finance and Collection Management and proved herself to be an extremely knowledgable and intelligent participant with that rare combination of also being delightfully charming and eloquent. She has a wonderful energy, drive, and passion for the work she is doing and a warmth and deep concern for the people she is working with”.

Professor Rachel Pownall, Art Finance at TIAS Business School and Art Business at Sotheby’s, London.

(Thomas Allen)

(Thomas Allen) -

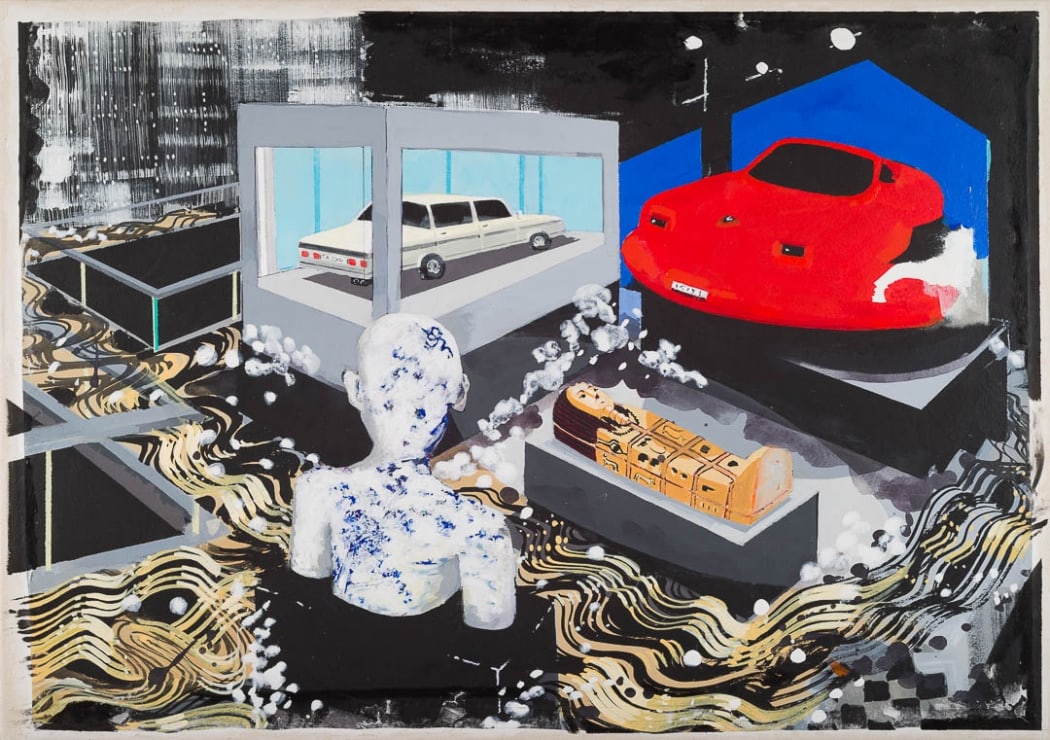

Essays from the exhibition catalogue, by Charles Saumarez Smith, Candida Stevens and Paul Bonaventura

Foreword - Charles Saumarez Smith

I first met Stephen Farthing when I was Director of the National Portrait Gallery. I was, for obvious reasons, interested in artists who investigate and stretch the conventions of portraiture in an intelligent way. I became aware of the work Stephen had done in the 1970s playing with royal portraiture, as in his Louis XV, now in the Walker Art Gallery, in which he teased the viewer by breaking down the components of Hyancinthe Rigaud’s of official portrait of the young Louis XV and treating them with deliberate irony, an idea which he correctly now considers as part of an early interest in the classic strategies of post-modernism.

Knowing that Stephen was Ruskin Master of Drawing in Oxford, I thought that he would be well placed to undertake a commissioned portrait of the founders of the major social historical journal, Past and Present, many of whom were themselves associated with Oxford, including Sir John Elliott, Regius Professor of Modern History, Christopher Hill, who had been Master of Balliol, and Sir Keith Thomas, President of Corpus Christi. He undertook the commission with great vigour, documenting his conversations with each of the sitters, enjoying establishing the network of their original relationships, and producing a group portrait which I still very much admire – a cool and cerebral depiction of the post-war, mostly Marxist, intellectual establishment.

Since then, I have kept in touch with Stephen as he migrated to New York as Executive Director of the New York Academy of Art, back to London and to Chelsea School of Art as the Rootstein Hopkins Professor of Drawing, elected an RA in 1998, and now the very active chairman of the RA’s exhibitions committee, which gives him an important role in overseeing the institution’s exhibitions policy. He is unusual as an artist in being so sociable, enjoying the politics of college life when he was at Oxford and as happy to talk about, and write about, the practice of art as he is to practise it himself.

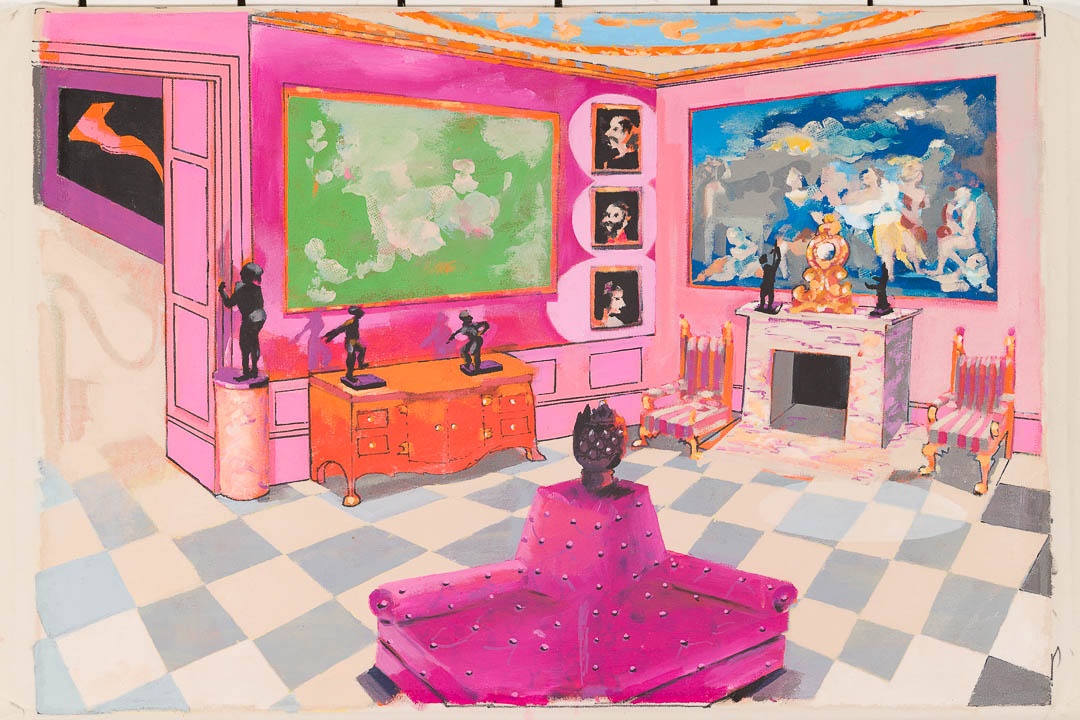

Now, in his exhibition Museums of the World, he is investigating the complex relationship between works of art and their setting – the way work is displayed and how the systems of display, including the lighting, the seating, and the display cabinets condition the way works of art are viewed. It includes a new version of a work which was shown in last summer’s annual Summer Exhibition, called Room 3, A Museum of Vernal Pleasure (2017). It is a depiction of Gallery 3 at the Royal Academy, the grandest of Sydney Smirke’s top-lit, 1868, beaux arts galleries, filled deliberately incongruously with versions of the work of currently well-known artists, including, most obviously, a large landscape by David Hockney and a pot by Grayson Perry. It is painted with Stephen’s particular brand of intelligent irony, faintly mocking the foibles of the art world, but with good will, not satire.

The other paintings in the series show a version of the Yale Center for British Art (but unimaginable with pink sofas), the magnificent clutter of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, 1, E 70th Street, the address of the Frick, and the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. They demonstrate Stephen’s worldliness, his ability to travel in the imagination, his knowledge of the conditions of art display, and the contrasts between the ways that art is displayed on different continents, in different milieux, in private and in public. Intelligent and knowing wit is not something which we normally look for in contemporary art, but it is evident in the work of Stephen Farthing.

Charles Saumarez Smith is Secretary and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy of Arts

A meeting of minds; artist and collector, art and collections - Candida Stevens

This extraordinary meeting of minds between artist Stephen Farthing RA and collector Simon Draper, also owner of Manor Place Museum, demonstrates the inextricable link between creation and collection. Each is a passionate pursuit, a form of creativity and expression that is practised with discipline, absorption and commitment. Both artist and collector hope to reveal and give meaning to their respective worlds and for me, from a curatorial perspective, the striking connection in the works created by Stephen and placement of his paintings in Simon’s museum, is an act that offers a most intriguing, insightful and genuinely immersive experience.

The idea of exhibiting part of this exhibition within a private collection was developed when Simon kindly volunteered Manor Place Museum, not far from our gallery, as a venue for a suitable exhibition. While working with Stephen on the production of his Museums of the World series, the association was obvious. His paintings study collecting and collections that guide us from the Cairo Museum, with its 4000 year old Ostrica drawings, to a recent assembling of works by contemporary artists at the Royal Academy Summer exhibition. The common references that exist between these two individuals have made for a fascinating dialogue about collecting, collections and their significance. Study at leisure the connections.

Art collecting existed in the earliest civilisations, Egypt, Babylonia, China and India. Precious objects were assembled in temples, tombs and palaces. Royalty were important in accumulating these ‘cabinets of curiosities’, almost anthropological assemblies of artefacts from travels. Collecting evolved into

its modern form during the Renaissance when it was associated with the patronage of the church, state and crown. By the 18th Century well-to-do homes were expected to contain fine objects from paintings to porcelain, hence a rise of collecting as a pastime. By the 20th Century individual collectors clearly represented a driving force within specific artistic markets and movements, whilst today it is increasingly common for collections to be built by corporations and institutions.On a macro level, public collections have a profound role to play in the communication and preservation of culture and its values. On a micro level, individual collectors can also have influence, through demand for a style of work, perhaps a commission. Sometimes the two link and many historical, private collections have been the beginnings of several of the major museums we know today. Major examples where few or no additions have been made include the Wallace Collection in London and the Frick Collection in New York, both of which Stephen has included in this series, The Museum of the Boudoir: Manchester Square, London, and The Museum of Domestic Wealth: #One E 70th St respectively. The role of collector and collections is shifting again. In this time of globalisation and digital acquisition the way in which art can be seen, preserved and bought has evolved dramatically. The traditionally, Western influenced art market is opening out and new collectors have begun to emerge in South America, Asia and the Middle East, where some of the earliest known collections began. It will be interesting to see if international, eclectic collections will develop and respond to this moment – perhaps even provide a new age for museums. Yet, for all these changes over the centuries, the behaviour of collecting remains largely the same. Acquiring art still grounds us to something tangible by which we are moved. It remains a deeply human and enduring activity, inspired by creativity and intellectual curiosity, and offers us a physical exploration and connection to both our collective and personal histories.

It has been a great pleasure to be instrumental in bringing artist Stephen Farthing and collector Simon Draper together. I believe the role of a curator is to present and create new and different ways of looking at and experiencing visual art and to remind us of the deep impression it can have on our emotions and thoughts. This exhibition allows us to do that and I am grateful to both Stephen and Simon for being so open to the idea. I felt it fitting that a final piece in the series should be created by Stephen of Simon’s museum at Manor Place, The Museum of Post-Cubist Painting: Near Chichester. It comes from the dialogue between us all and is a pleasing edition to a body of work that will no doubt be meaningful for many.

Interestingly, there are a number of personal links between the paintings of the museums in this series and those who have been involved in the exhibition. Of course, for Stephen his link is to all the museums featured but perhaps mostly the Royal Academy, where he is an Academician and current Chairman of the Exhibition program. For Charles Saumarez Smith, to the Royal Academy, where he is Secretary and Chief Executive, as well as the National Gallery where he was previously Director. For Paul Bonaventura, it is the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology from when he was the Senior Research Fellow in Fine Art Studies

at the University of Oxford. For me, it is serendipitous that The Wallace Collection is included;a collection that I was taken to visit aged 11, recalling the first time I became truly spellbound by visual art and moved by an associated journey into our history. We may each have just such a moment; I hope Stephen Farthing’s Museums of the World will remind you of that.

Les musées imaginaires - Paul Bonaventura

In museums things are anointed with a cloak of specialness. To some extent this aura comes from their designation as part of a collection, where each object is enriched by the company it keeps... Museum objects are distinguished by multiple layers of histories... [and their power] also rests in the fact that they are pregnant with potentially new information and new insights. So while museums keep things as physically unchanged as possible, they also invest a lot of energy into augmenting their meaning.

Ken Arnold, A House for the Curious

A couple of years ago the Picturehouse cinema chain screened a short documentary called See everything in which the American lmmaker Alex Gorosh attempted to see every piece of art in London in one day. The film was commissioned to promote the Art Fund’s National Art Pass and showed Gorosh sprinting through the capital’s museums and galleries on what was clearly a mission impossible – a race against the clock with only one outcome. Bagging more than 140,000 pieces across thirteen locations, from the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the east to the Victoria and Albert Museum in the west, Gorosh certainly has claims to being a record-breaker when it comes to seeing the most art in a day. Yet London’s museums and galleries allegedly contain more than 20 million items so he racked up less than 1% of the total.

The climax of his art-driven marathon finds Gorosh at the National Gallery. Realising that he has nowhere else to be he finally slows his pace and starts looking at the collection more closely, halting in front of Georges Seurat’s luminous Bathers at Asnières. At which point he reaches for the consolation of philosophy and alights on an observation by high-school slacker Ferris Bueller: ‘Life moves pretty fast and if you don’t stop to look around once in a while you could miss it.’

To my way of thinking there is a little of See everything in Museums of the World, Stephen Farthing’s newest group of paintings. While implicitly acknowledging the hopelessness of their respective ambitions – see everything locally, go everywhere globally – the filmmaker and artist are locked together

in an obsessive relationship with the temples of art. Moreover, in their restless quest to update their lists both men owe something, at least, to Jules Verne’s classic escapade Around the World in Eighty Days.Verne’s peripatetic novel was published in 1872 and marked the end of the age of exploration and the start of the age of global tourism. During the course of the 19th century technological innovations in rail and sea transport opened up the possibility of rapid, affordable travel such that anyone could now sit down, draw up a schedule and embark on a journey of personal discovery. Three thousand years after Homer’s seminal tale of a voyage interrupted, Around the World in Eighty Days crystallised the concept of time as theme in the modern world.

While Museums of the World is self-evidently about place and space, it too is about time. Not just the time it took Stephen to identify and visit the institutions that figure in the paintings, but also the time he invested in imaginatively reconfiguring their structure and contents. Plus the time it takes us as viewers to pick them apart. Rich in detail, the Museums don’t work if we have any form of attention deficit. As Stephen says, you’ve got to lose yourself in them just as you lose yourself gazing into a crackling log fire. On a visit to his London studio last summer, Stephen explained to me that all the canvases in the series were painted over the past two years in Mexico City, where he found himself living with his wife and family. Some of them connect with the much larger museum paintings that he was making in New York City from just after he moved there at the turn of the millennium, but the rest have no backstory and simply relate to what he is looking at and thinking about now.

Stephen wanted his new Museums to be small partly for practical reasons – the difficulty of selling large pictures, of not having a big studio, of frequently being on the move – and partly because he felt like painting sitting down. In playful riff on Henri Matisse’s declaration that he wanted his art to be a calming influence on the mind, ‘like a good armchair’, Stephen has turned his vocation into a sedentary activity.

‘These days’, he admits, ‘I paint in what is effectively a library. There are books all around the easel and I sit in an armchair to paint. I maybe have three canvases on the go, but I do one painting at a time and turn the rest to the wall... It’s less about making in a studio and more like writing a letter, but I can’t write straight off. I have to self-edit on the computer all the way through because writing doesn’t come easily to me. I’m nearly always engaged in a process of refining a piece of writing and it’s the same with my painting. I’ve come to enjoy the actual mechanics of building a picture and not doing it in the workshop atmosphere of a traditional studio.’

The fifteen pictures that currently make up Museums of the World were cut from their original supports for shipment to London and re-stretched on larger supports because Stephen didn’t want the paint to reach the edge of the canvas. ‘It’s such hard work not painting to the edge,’ he confesses. ‘It requires a kind of restraint that doesn’t come naturally to me. I’ve always painted to the edge in the past so this is a new conceit.’

Stephen regards his Museums as maquettes or models. When the occasion arises – through a commission, for example – he can paint one on a much grander scale and then he doesn’t worry so much about the edges. The one big painting that has already come out of the series is Room 3, A Museum of Vernal Pleasure, which is a re-working of The Museum of Vernal Entertainment: London. Stephen painted the larger of the two canvases for Room 3 of last year’s Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts and it features on the front cover of the catalogue for the show. ‘In both paintings,’ he confirms, ‘I’ve got a back view of a Michael Sandle sculpture and I’ve played it off against a David Hockney on the right and a Rose Wylie to the left. And I’ve turned the Zaha Hadid architectural model into a massive sculpture. Likewise the Grayson Perry pot. In the distance there’s a painting by Paul Huxley and a painting of mine.’

By including his own work in the two pictures, Stephen expresses a sense of belonging – to the Royal Academy of Arts, to the world of contemporary British art – and this sense of belonging pervades all the Museums. Stephen is the guide by which we enter these institutions. Making a pattern out of a muddle, we

see their collections and exhibitions through his eyes and the works that he has chosen to depict constitute a striking canon of achievement.Many of the preoccupations that surface in the Museums were flagged up in two of Stephen’s earlier travelogues, which were given over to fanciful portrayals of major cities from around the world. Like The Knowledge and Falsifying the Log, the Museums represent two kinds of journey – one geographic, the other artistic – and we can trace the provenance of some of his techniques right back to his room-based paintings of the early 1980s, such as Mrs G’s Chair and The Nightwatch.

‘Over the decades I have got better at painting,’ Stephen says. ‘I don’t necessarily make better paintings, but I’ve got better at the craft of painting and I’m more inclined to take risks. I think this body of work is less manufactured than some of my earlier paintings in that I’ve taken more late risks with them rather than the risk being at the beginning of the process. I’ve tended to start with a tight little subject and then wrecked it later on... I enjoy mixing up colours and sticking them on. It’s physical pleasure and when you get that right that experience transfers to the viewer and they get physical pleasure too.’

In the Museums anything that looks like artistic bravado has been manufactu- red and there is always some kind of diversion from the art on display. ‘The gallery is about showing art,’ he says, ‘but what I’m also showing is a distraction in the gallery. So around the frame of the window in the Whitney, for example, I’ve used a fluid medium to depict dampness or rot as a way of bridging the space between the depicted artwork, the wall and the floor. It’s a softening device.’ The licence that Stephen has allowed himself in his Museums – the modi ed gallery plans, the repositioned artworks – carries over into the titles.

Cheekily irreverent, the titles reformulate the mission of the institution. Thus the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York morphs into The Museum of a Slice of America: Madison Ave, the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City becomes The Museum of Precolonial Imagination: Chapultapec, the Wallace Collection in London turns into The Museum of the Boudoir: Manchester Square, London and so on.

Stephen traces the idea of re-titling his paintings to a 2016 visit to the Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart. Described by its gambler founder as a subversive, adult Disneyland, MONA presents antiquities, modern and contemporary art from the David Walsh collection. Stephen sees the building, which is largely underground, as an Aladdin’s cave of cultural treats, but says there is no clear logic to the display – hence The Museum of the Each-Way Bet: Hobart.

While I sip my way through a second cup of coffee, Stephen shows me the finished canvases that will go into the exhibition with Candida Stevens Gallery. I’m particularly struck by his interpretation of Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware in The Museum of the American World View of Global Visual Culture: Manhattan. Stephen has previously made several copies of Leutze’s masterpiece in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but in this instance elements of the highly ornate frame have been given an opportunity to float free and they dominate the space of the painting. ‘Every now and then,’ he affirms, ‘your mind wanders in galleries and you let the pictures take you over.’

Around the time that Alex Gorosh was roaming the halls of the National Gallery, camera in hand, Stephen was putting the finishing touches to The Museum of Good Painting and Good Frames: Trafalgar Square. I think the two Vermeers on the back wall are terrific and Stephen is particularly pleased with his rendition of The Fighting Temeraire that does a great job of capturing J.M.W. Turner’s swirling brushwork. He’s also managed to transform George Stubbs’s iconic portrait of a rearing Whistlejacket into a jaunty pub sign.

Stubbs crops up again in the Yale Center for British Art a.k.a. The Museum of Art From A Small Island: New Haven. ‘I painted Stubbs’s Zebra first,’ he says, ‘and then drew a rectangle around it, which became the frame, and then drew another rectangle around it, which became the wall. And then I put in the grey floor and the light source. After which I painted the pictures in the background and finally the ectoplasm. Like the painting around the window in the Whitney picture, this loose handling is a way of me getting some of the energy out of the depicted painting and onto the depicted floor. It’s an attempt to give the zebra somewhere to go if it ever decided to jump out of its frame.’

As Stephen pulls out painting after painting I suggest that the maquettes add up to an index of nearly all the museums and galleries that he has visited over the past twenty years – the venues that have had the biggest impact on his thinking and development as an artist – and Stephen agrees: ‘The underpinning

principle goes as follows. You arrive as a stranger in a foreign city and you are looking at a way to relate to it. The museums and galleries are the places that I naturally gravitate towards, feel comfortable in, and want to spend time in. You can just sit there and look at the people and the art and try and work out how you’re going to fit in. In very practical terms it’s a way of me trying to integrate myself into a new environment.’

Being the trailing spouse of a US diplomat, and before that a regular fixture on the British Council exhibition circuit, Stephen is more travelled than most and is very much at home around world culture. It doesn’t always transpire that travel broadens the mind, but in Stephen’s case it does. Indeed, there is something surprisingly uplifting about his ritualistic acquisition of the world’s museums in paint. Although the process represents an act of possession, that ownership speaks of a deep-seated love affair and a profound and benign enchantment with artists and artworks from other times and other places.

-

GOOD NATURE - A CELEBRATION OF THE NATURAL WORLD

31 invited eminent and emerging artists make a new work in response to the theme.Candida Stevens Gallery in the UK presents its major show GOOD NATURE this September. It celebrates the natural world through the observations of some of the leading artists working in the UK today who awaken our senses to the abundant beauty of our planet.

They take inspiration from the warmth of the sun, the green lungs of the forests and the dark depths of the oceans, alongside all life that teems in and under them. We are reminded of the changing and fragile state of Earth and are invited to reflect on how it is necessary for all these elements to interconnect in order to exist.

GOOD NATURE – a celebration of our planet, its beauty, its fragility and the essential part we all play in its preservation.

31 invited eminent and emerging artists make a new work in response to the theme.

16 September to 28 October 2017

Tuesday- Saturday 10am – 5pm

CANDIDA STEVENS GALLERY Chichester West Sussex PO19 1BA

Sunbathers, 2017 by Alice Kettle

Candida Stevens, curator of the gallery has invited 30 artists to contribute and respond to the theme with new work. "I chose to bring together these artists to concentrate our thoughts around the planet at a moment when its beauty and fragility are deeply affected by our treatment and explorations of it” she said.

GOOD NATURE is curated to be a thoughtful and probing look at place in the natural world and her hope is that in asking artists and thinkers to respond to this important theme it will create positive reactions from those who come to see the work and encourage them to make changes for the long term conservation of our world.

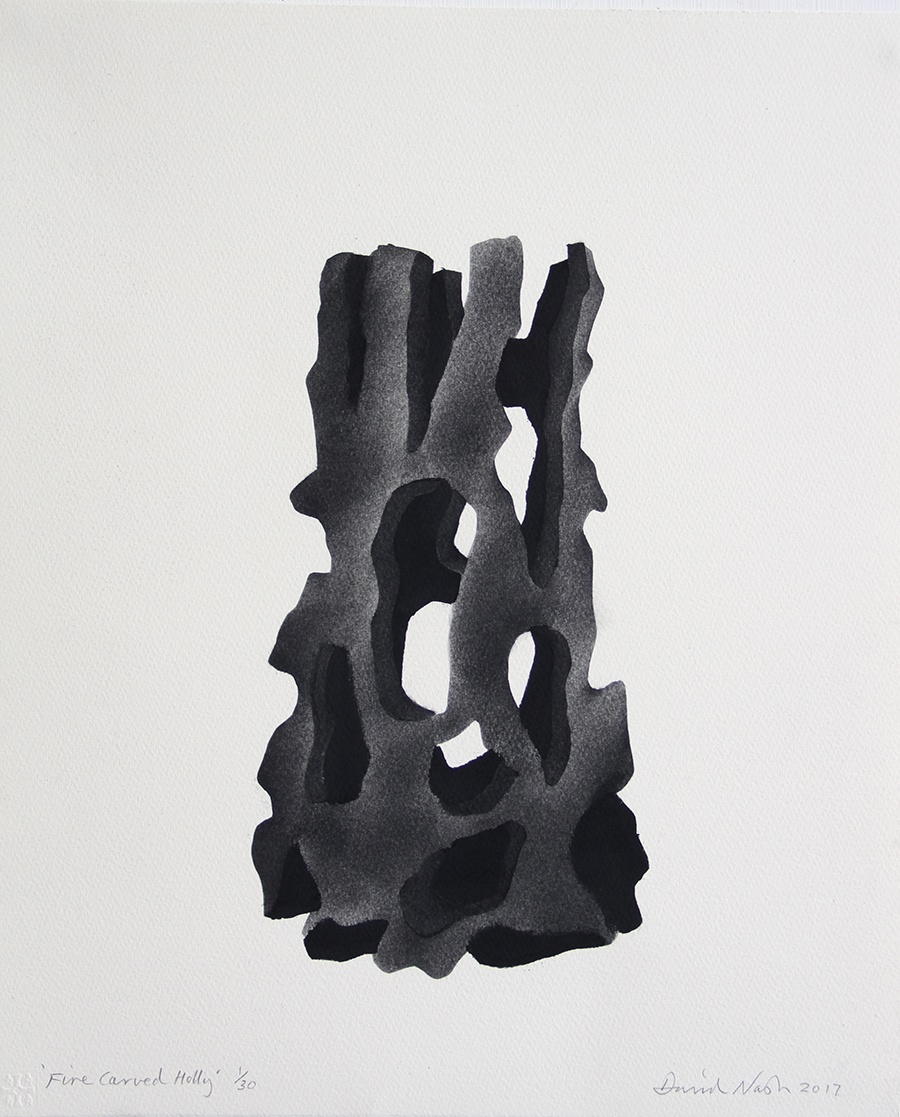

Holey Holly, 2017 by David Nash RA OBE (The sculpture will also be shown during the exhibition)

The theme has captured the imagination of several eminent British artists including highly acclaimed Royal Academicians, environmental sculptor David Nash RA OBE with a new piece created from a Holly tree, charred in his distinctive style, Eileen Cooper RA OBE, and this year’s curator of the RA Summer Show, with a painting inspired by the domestic use of nature and Stephen Farthing RA who contributes a new print about the escapism nature provides.

Perfume, 2016 by Eileen Cooper RA OBE

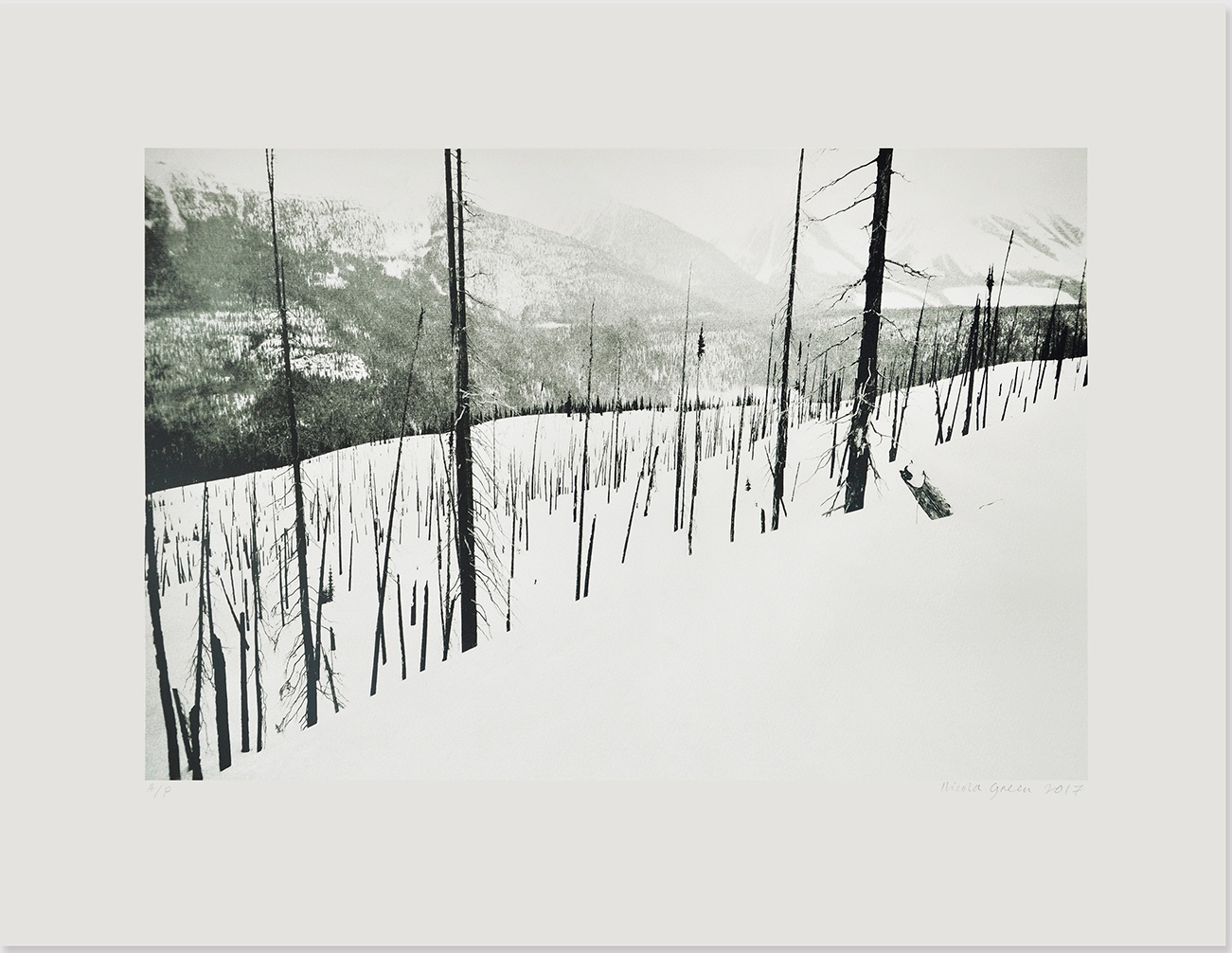

Other notable responses come from Stephen Chambers RA and Nicola Green who both return from highly successful exhibitions at Venice Biennale with new work that probes the acts of humankind on nature.

Chambers humorously comments that “When Professor Sir David King in 2001 incensed George Bush by saying that global warming was a greater threat than global terrorism he was not kidding” and adds that his painting is “… not to attest to that truth. It is an image to acknowledge that were all things equal the result would be: Nature 1 Mankind 0”.

The Sense of Humour House, 2017 by Stephen Chambers RA

Nicola Green meanwhile has made a series of silkscreen prints in response to deforestation that she says she has “…always wanted to do but never had the right opportunity to create until now”.

Sin Wati & Golden, 2017 by Nicola Green

Candida felt that this year seemed a pertinent moment to choose to look at nature. Not only is it a source of inspiration for many artists with whom she works, and a place she says she personally goes to for rejuvenation, but it is also a subject at the heart of the global agenda. She comments “We find ourselves in a profound moment, where this vital, if conflicting, conversation is taking place and choices are being made about how we use, and protect, our planet for the future”.

For her though, despite this being an age where our tendency is to sensationalise the horror stories about our environment, she wants to offer a positive message and show that there is still much to celebrate.

This was thought that grew during the course of her research for the exhibition when she discovered that there are also reasons to be hopeful. “Whilst I know that there are plenty of pillagers burning the Amazon forests and vast over fishing of our oceans, there are also those who can inspire. In preparing for this exhibition, I have met, read stories about and been motivated by people who fight their corner and dedicate their lives to studying, conserving, recording and ensuring that we continue to preserve and care for our natural world”.

It is in this spirit that she has curated GOOD NATURE. It seems that these good vibes have rubbed off. Tom Hammick, responds with an atmospheric painting inspired by the power of what lies beneath the Earth’s crust, pioneering textile artist Alice Kettle makes a piece about the power of the sun, whilst in contrast the photographic lens of Maciej Urbanek draws attention to the beauty found in the shade of the forest.

Smoke II, 2014-15 by Tom Hammick

Wildlife observations include a new bronze of boxing hares, by award winning sculptor Hamish Mackie. The vulnerability of natural materials is addressed with an inverted marble sculpture from Almuth Tebbenhoff. Planetary landscape artist Michael Benson investigates new worlds with a look at Earth from the Moon.

Boxing Hares, 2017 by Hamish Mackie

One interesting creative development came from science inspired Briony Marshall who ended up going on a new exploration with her work as a result, of the theme. Taking inspiration from the words and work of influential conservationist Rachel Carson “Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature - the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter” she created a sculpture out of compacted earth, a medium that is directly from nature, and one in which she has not worked before.

Earth Time & Disruption, 2017 by Briony Marshall

In all, the work of over 30 selected artists can be seen, each individual but responding to a common theme. It is one that is undoubtedly an important and increasingly relevant theme for our time. Candida comments of the artists responses that “many common themes pervade and I noted that the desire of the artists’ was to expose not only the vulnerability but also the constancy of nature”.

The gallery has also invited natural world explorer, and author of Natural Navigation, Tristan Gooley to write a foreword to the exhibition and provide a talk. He knows, from his years of experience, that giving talks that lecture people on the environment is not the way to engage them rather it is inspiring them that elicits enthusiasm to be proactive. “We shouldn’t lecture people into changing behaviour, it is almost always ineffective. Instead of saying, “Bird numbers are decreasing, this is terrible, we are all wicked and our lifestyle is an abomination,” we could try saying something very different. Maybe: “Have you noticed how the birds on trees and rooftops face into the wind? When they change the direction they are facing it means that the wind direction has changed and there may be rain on the way.” A person who enjoys this sign will come to notice the birds and any change in their numbers and behaviour.” Tristan Gooley, extract from the foreword written for the catalogue.

GOOD NATURE is a major show that unashamedly aims to take inspiration from all that is good about nature and hopes to bring out the good in all our natures to positively play our part in its preservation.

- ENDS -

-

Hamish Mackie

An interview with the UK's foremost wildlife sculptorHAMISH MACKIE ( b.1973)

Interview by Kerry Betsworth

Photography on site at the foundry in Oxfordshire by Dan Stevens

“Sorry, can I call you back I’ve got a tractor just arrived who’s delivering a horse”. It turns out later that this is one of his spectacular, bronze sculptures of an Andalucian Stallion which is going off to be placed at Stowe House. When he calls me back, we clear up the confusion – no not a real live horse - and laugh about how every artist needs a tractor. The quick-speaking, energetic and affable Mackie then begins to shares his thoughts on taking part in GOOD NATURE.

Hamish Mackie is an artist who doesn’t skate on top of nature, he is deeply rooted in it, experiencing and in contact with it on a daily basis. He grew up on a farm in Cornwall and has the practical knowledge of what it is to be part of and survive in nature. He tells me of early memories of a cockerel’s death where he became mesmerised by the anatomy of the bird, and was moved to sculpt it at school. He tells too the tale of a calf with a twisted gut that his father gave him responsibility to care for and rehabilitate. The 12 year old Mackie remembers fondly how the calf would follow him all over the farm, even up to the top of the hay stacks – ‘besties’ he says.

Later, his fascination with wildlife grew and became the major influence for his work as sculptor. Since 1998 he has travelled widely to observe, draw and sculpt wildlife in some of the world’s most remote landscapes. He lists Africa, Australia and Antartica as continents he visits to observe a vast array of wildlife. He is a 21st century explorer with an aim to capture a moment of a wild creature’s existence in its own environment.

This is something Mackie considers himself lucky to be able to do. Artists in the past would have to go to the zoo but now he can observe animals in the raw, living and responding to the natural world around them. He sees the landscapes as fundamental to how an animal exists and survives. Both co-exist and when it is correct “Nature is nature” he states “It is neither good nor bad, it just is”. The essence of his work is capturing this honest, if fleeting, moment.

He is not apologetic in that he believes there is a need to conserve the wildlife and natural kingdoms. He talks about his long and deep interest in the elephants he has observed in Liuwa, Africa. He comments that huge strides have been made in environmental practice from the days when he first travelled there over 20 years ago. Then they were unreconstructed cattle farms, driven by commerce. Now those farms have become environmentally focused, empowered to conserve and protect. TUSK is an organization that he has always supported, driven by his experiences and observations of human and wildlife in conflict there.

The natural world outside our shores may seem spectacular with its powerful tigers, lions and rhinos but he comments that there are wonders close to home too. We talk of his recent trip to the Isle of Ulver, where he took time to study deer.

His piece for GOOD NATURE is a pair of boxing hares. For him, hares are an enduring and much loved image of the English landscape and one that is as important to him as the elephants in Lowea.

He tells me that he regularly re-visits the subject, attracted by their dynamism and athletic shapes. “I use my interpretations of hares as a benchmark for my artistic development and technical scope”. This piece has provided him with an opportunity to ‘take bronze casting to its structural limits’. The light-footed hares are mid-kick with limbs only contacted in two places.

I ask him if the he thinks artists have a role in bringing nature to our attention and highlighting its shifting affects. “Yes” he simply states. Artists have long taken inspiration from nature and the natural world and without it there wouldn’t be a channel through which to create. He feels they have a duty of care to reveal its beauty and fragility. In doing so the next generation too can find inspiration - “It would be criminal to let it go on our watch” he says.

He does though hold out some hope for the future and thinks that the human race is slowly waking up to the realities and consequences of preserving nature. For him, the demands of his studio and the making of work in the foundry have meant that he cherishes his time in the wild all the more. In his view there’s too much rushing today and it can mean we miss out on what’s going on in the environment. Humans need to get back to the place they originated and take stock.

April, 2017

-

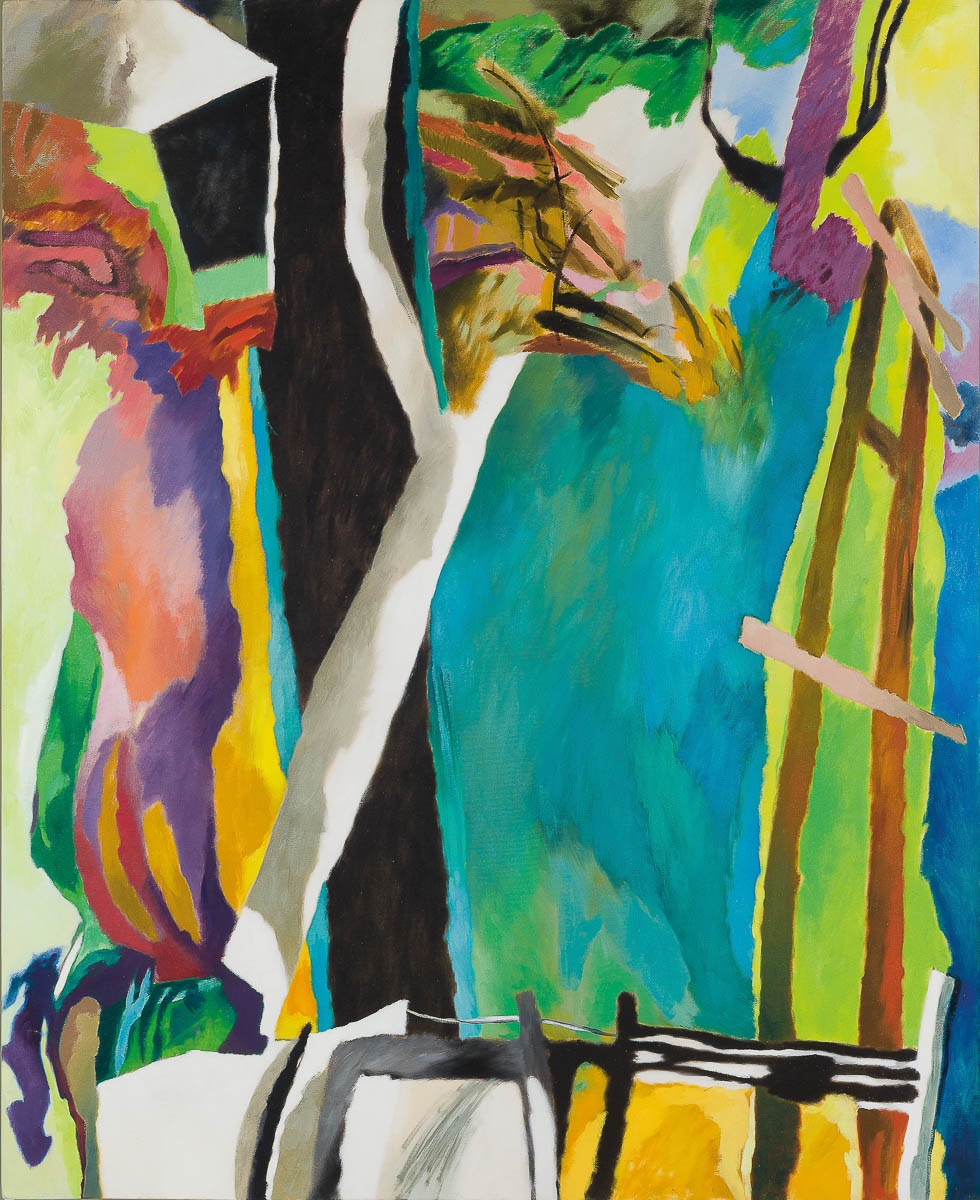

Pippa Blake QUEST

27 May - 17 JuneTouched by the pathos of humanity in the world we inhabit, here is a body of work deeply felt and observed. ‘Yearning’ is a word that resonates with nomadic artist Pippa Blake, and it’s not hard to see why when you view her soulful, touching paintings. Her work often lingers in the darkness, as small pools of light appear and illuminate or ignite a curiosity about her chosen subject. Blake is constantly searching as she investigates and explores her vision of the world.

QUEST, seems an apt title for her solo show, which takes a look at a body of work from the last ten years. Her subjects are inspired by dramatic geographical and man-made features; from gorges and wastelands to figures glimpsed. Her enigmatic paintings evoke a sense of mystery and mood and for her they “are outer expressions of her inner feelings”.

Blake’s work is immensely atmospheric, perhaps melancholic but there is something always exquisite in the moment or scene that she captures – a soulfulness. Her work is able to suspend us in a place where reflection and stillness can happen. “I have always felt deeply. Light and dark is integral to my work. I look to the horizon and am fascinated by what might be beyond”. Many of her pieces are observed from a distance, often on travels – in cars, aboard planes, on walks – the world Blake shares with us is one that is seen to be going on about us but one in which we only watch, peripheral, not disrupting, hidden.

This is in contrast to the way in which Blake makes her paintings. She comments that she “loves the physical process of gestural mark making”. She tells me that she puts her whole body into it – left to right, up and down - the larger the canvas the better. For her painting is a very visceral and immersive act and this commitment remains vital to her practice. Music too fuels her creativity and she has a passion for blues, jazz and Bach. Her current obsession, in the studio, is Wagner’s overture to Tannhauser.

Art has always been part of Blake’s life. Her grandmother and mother were both potters and artists and she was encouraged from an early age to be creative. Her childhood on the shores of Chichester Harbour was spent messing about in boats, walking on the South Downs, and today remain places that fuel her work. She attended both Camberwell School of Art and later West Dean College. She sites Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and Richard Diebenkorn as influences and her early abstract art school work was influenced by an exhibition of Islamic art at the Hayward Gallery.

A critical moment came for her when her then tutor squared off an inch of wall “and made me sit and paint it”. I suddenly realised I was making a painting and that it was totally valid as a piece of work”. Later, her MA tutor Dr. Ed Winters was pivotal to her artistic development as she began to move towards an aesthetic inspired by words shared with her “The landscape can be but a metaphor for the mind and its contents”.

Blake is something of a rover and adventurer so it was no surprise when life found her criss-crossing seas and continents, at times living on boats and making other lands her temporary home. In this time, she experienced both deep personal joy and pain, which has sometimes spilled into public life, with the tragic death of her much admired husband, yachtsman Sir Peter Blake.

Throughout her life though, she tells me that she has always felt drawn to the darker side of the human experience. She was much affected by the poetry of the war poets, particularly one of her literary heroes Wilfred Owen, at school. A line from his poem Strange Meeting has long resonated with her and war is a theme to which she continues to return. She was recently appointed artist in residence for Chichester Festival Theatre to respond to the play Someone Who’ll Watch Over Me that explored a hostage experience. Today she continues to watch, collect and remain fascinated with the images of conflict in the Middle East and the response and reaction of the people it affects and the adversity they face.

Journeys are also a repeating theme for Blake. Her Road series, was inspired by drives at night to and from West Dean College. She was touched by the loneliness of travelling in darkness. Recent travels have led to the creation of her newest series Flightpath. She comments that so often “we zoom past the world but for me, when I’m in the air, I am acutely aware that there is a whole world down there and people getting on with their lives and dramas”. The poignancy of this thought, and the unknown circumstances or conditions of the people below, are what she feels moved by and is expressing when she paints.

Blake’s mastery of mark making, gestural strokes and the suggestion of form and line are evident across the work. She tells me that she has a sheer love of paint, always oil, for its “…quality, richness and texture” and intuitively mixes her colours to get the tonal effect that helps to give her work such mystery. For her painting is not easy and she comments that “I constantly question why I do it. People often say it must be relaxing to be able to paint but for me it is a struggle but one that I can’t help doing’.

This show may be something of a crossroads for her as she contemplates where she will go next, not just in the world but also with her painting. She sees it as a wonderful opportunity to overview her work and is curious as to what questions or answers it may draw out. So, just for a moment, we shall suspend here, somewhere between the light and dark, and take time to see what might be revealed before this remarkable painter continues on with her quest.

-

Nicola Green - SOLO

In Seven Days... & The Dance of ColourWe are delighted to welcome back to the gallery Nicola Green, a contemporary artist with a unique eye focused on the movements and people that lead and represent us in modern times. She is forensic in her observation, questing in her curiosity and unceasing in her commitment to creating and gathering vast visual records on each of her subjects before she enters her studio to create the portrait, or series, that she seeks.

-

-