‘Thread is transformative,' says Alice Kettle, winner of the Brookfield Properties Craft Award 2023

INTERVIEW MEENA SEARS

Textile artist Alice Kettle has been awarded the fourth annual Brookfield Properties Craft Award, a prestigious prize granted in collaboration with the Crafts Council at Collect art fair. With more than 400 makers and artists in the running, Kettle was selected for her significant contribution to the national story of contemporary craft.

Internationally renowned as a pioneer in textile art, Kettle defies expectations of her medium through the unprecedented scale of her work. Her unique combination of machine and hand embroidery builds tiny individual stitches into sweeping, painterly lines that deceive the eye. With a career spanning four decades, she often draws attention to political issues in her textiles, from the personal to the wider, shared experience. ‘Thread is transformative,’ she says. ‘We can mediate the difficulties of our world through thread if we open our minds to alternative ways of doing things.’

As part of the award, Brookfield Properties has bought three of Kettle’s pieces to enter into the Crafts Council’s national collection – a major public asset that has acquired more than 1,700 works since the 1970s, including one of Kettle’s pieces from 1988. The artist has also been supported in staging a solo exhibition showing across two of Brookfield Properties’ central London venues, 99 Bishopsgate and 30 Fenchurch Street.To Boldly Sew contains the three pieces that are now part of the Crafts Council’s collection, as well as a selection of Kettle’s most significant and impressive works, demonstrating the artist’s technical proficiency and dedication to the advancement of textile art.

We caught up with Kettle to talk about her award, and how she believes that ‘thread can change the world’.

Brookfield Properties Craft Award winner Alice Kettle in her studio. Photograph Alun Callender.

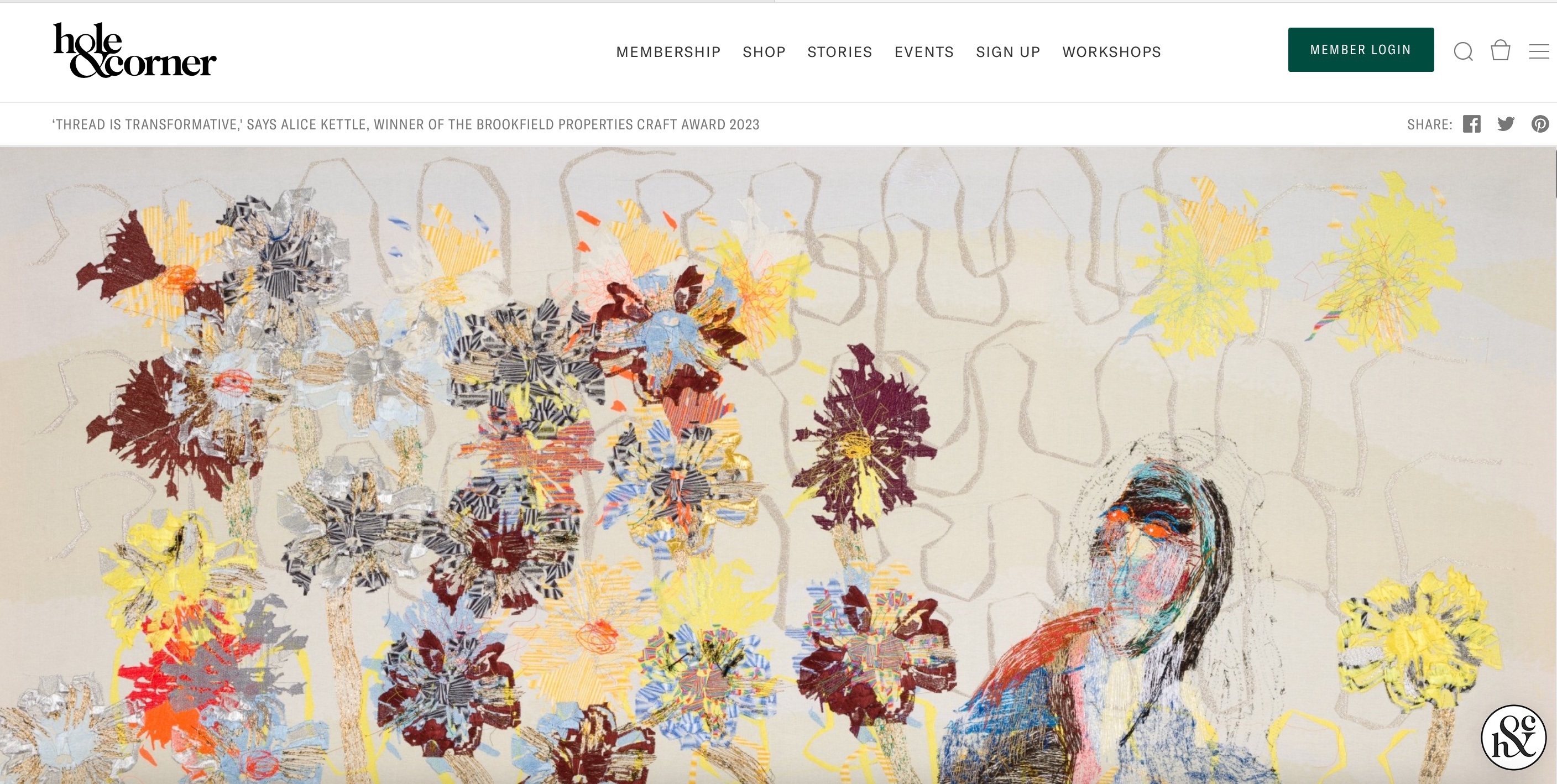

Hero image: ‘Vira in my garden’ by Alice Kettle. Photograph courtesy of Candida Stevens Gallery.

What does it mean to be awarded the Brookfield Properties Craft Award?

I’m so proud. I never win anything because I often feel that my work doesn’t quite fit anywhere. But I truly believe that stitching is transformative, and I’ve committed my life to it, so to be acknowledged by the Crafts Council, my professional body, feels like a really powerful thing.

Brookfield Properties are also doing so many amazing curatorial projects both nationally and internationally and it’s an honour to feel part of that. Craft sits slightly on the edge of the arts, and it’s always had to kind of force its way in, so being given a platform to push it out there is amazing because it’s not just about me, it’s about building the practice for the community.

Could you elaborate a bit on how you feel embroidery can be a transformative practice?

Making is incredibly empowering because, when you’re making something, you’re making something more, you’re making something good, or you’re making something better. I think the thing about textiles more specifically is that it’s ubiquitous so it’s less threatening than other arts and crafts; people can relate to it because it crosses the border between the domestic and the artistic. So embroidery can be a particularly effective way of empowering people.

Alice Kettle with ‘Sea’, a 300 x 800 cm textile panel exhibiting as part of To Boldly Sew at 99 Bishopsgate. Photograph David Parry

Are there any pieces in this exhibition that demonstrate the power of stitching?

This big piece here [points to ‘Sea’] is part of a social justice project I did (and am still doing), called Thread Bearing Witness. I wanted to work with refugees and asylum seekers to show how textiles could be used to create social bonds, document stories, and raise awareness of issues. And actually, textiles are a really interesting way to encounter this particular issue because textiles, throughout history, have always migrated – through trade. They move around in patterns carrying the voices of those who made them, voices that are often marginalised. So I did this project to represent the marginalised voices of refugees.

Alice Kettle with ‘Sunflowers’, which is on display at 99 Bishopsgate. Photograph by Vicky Polak

I worked with thousands of people on a number of different projects including bag-making workshops, and large collaborative pieces like ‘Ground’, ‘Sky’ and ‘Sea’. For ‘Ground’ and ‘Sky’ I asked people from migrant groups to send me an image, which I represented through embroidery. ‘Sea’ is the only panel in the triptych without direct contributions; it is a bird’s eye view of migrants crossing the sea, based on press images.

I wanted to create a space to elevate human dignity; to say that this is a story that is tragic and complex, but it is also resonant and beautiful, in terms of each individual person. Embroidery is a common language that we all have access to; it transcends cultural differences. And so, through the Thread Bearing Witness project, each person became a part of a story and, collectively, we made something beautiful. I wasn’t offering a solution, I was just saying this is what it is.

How did you curate ‘To Boldly Sew’, and what has the response been like so far?

Saff Williams, curatorial director for Brookfield Properties says:

I think that Alice’s work has this kind of monumentality in scale, in terms of size but also, as you’re hearing, in terms of breadth, depth, and the conditions of the work. I really wanted to get that across in the exhibition. We’re working in a non-exhibition space of course, but actually, it has so much light and room it’s almost like a gallery, so I was keen to make sure we got ‘Sea’ in here.

Since we’ve been installing, we’ve noticed people seem to be quite shocked by the pieces. People keep coming up saying, ‘I’m really interested in looking at these paintings’ because the assumption is that works of this scale would have to be painted, and also Alice’s linework makes the stitches look like brushstrokes from afar. Then, when they see it’s embroidery, they’re dumbfounded.

As Alice said, everybody has a connection to embroidery, but it tends to be quite private, like your grandmother’s tablecloth you use at Christmas, and not a seven by three metre piece of cloth. So there are lots of questions about how’s it done and how long it takes. People are very concerned with time; they think there’s something special about the length of time it takes to do embroidery – especially now that everything’s so quick.

Alice, how long does it take to complete a piece?

It is slow. ‘Sea’ took me about seven months.

Your work has been called ‘pioneering’ and ‘uniquely hybrid’; can you explain your techniques to me?

I switch between machine, hand and digital embroidery. For the machine stitching, I take the foot off the sewing machine and use the needle like a pen, moving the fabric around freely to create quirky drawn lines. Then I can loosen the top threads to make changes in the looping. It’s all the things you’re not really meant to do with a sewing machine.The nature of my practice means that I have to do it upside down and in reverse; so all of this is done from the other side. It’s unpredictable and I go wrong quite a lot but I kind of like that – and you can always cut it out and go back in with patchwork.

The Crafts Council already has one of your pieces from 1988; can you explain how your craft has evolved over the years?

I used to stitch over the whole thing, but now I tend to do a painting and print it onto fabric, then stitch over that. I like the spatial quality that it brings to the piece.

Brookfield Properties purchased ‘The Swimmers’ by Alice Kettle as part of the prize. It is now part of the Crafts Council’s national collection. Photograph courtesy of Candida Stevens Gallery

‘Bather’ by Alice Kettle. Photograph courtesy of Candida Stevens Gallery

You studied Fine Art at the University of Reading; how does your background in painting inform your current practice?

I trained as a painter at the end of abstract expressionism, so it was all about gesture, mark-making and colour. I think that has set me in good stead for what I do now and shaped how I approach my textile work. I’m really interested in colour relationships and layers; I like the way that embroidery has a substance to it and a kind of conversation with light. You’re not mixing colours, you’re just putting two colours together, and they can be different qualities of thread – if you put a shiny thread next to a matte thread, one will float off the other and you’ll get different tones according to the changes in light.

You teach Textile Arts at Manchester Metropolitan University; how do you see the younger generation approaching craft differently, and what excites you about craft today?

People are engaging with craft in ways they never have before; people are more interested in the haptic and the physical, and in ways of using tools and materials in our everyday lives. I think the pandemic has had something to do with that. There’s a return to more traditional crafts, such as customising your own clothes, which is really exciting. But on the flip side, I think the possibilities that technology brings are also really interesting; I see a lot of my students using traditional skills but reinventing them using new technologies.

I also see a lot of my students thinking about how we can use craft for social engagement, and how craft can serve a wider cause. I think that’s a really powerful way to position craft in the modern world.

‘To Boldly Sew’ is open until September 29 at 99 Bishopsgate and 30 Fenchurch Street; entry is free

Alice Kettle has also co-curated an exhibition at the Arnolfini in Bristol; ‘Threads: Breathing Stories into Materials’ runs until October 1