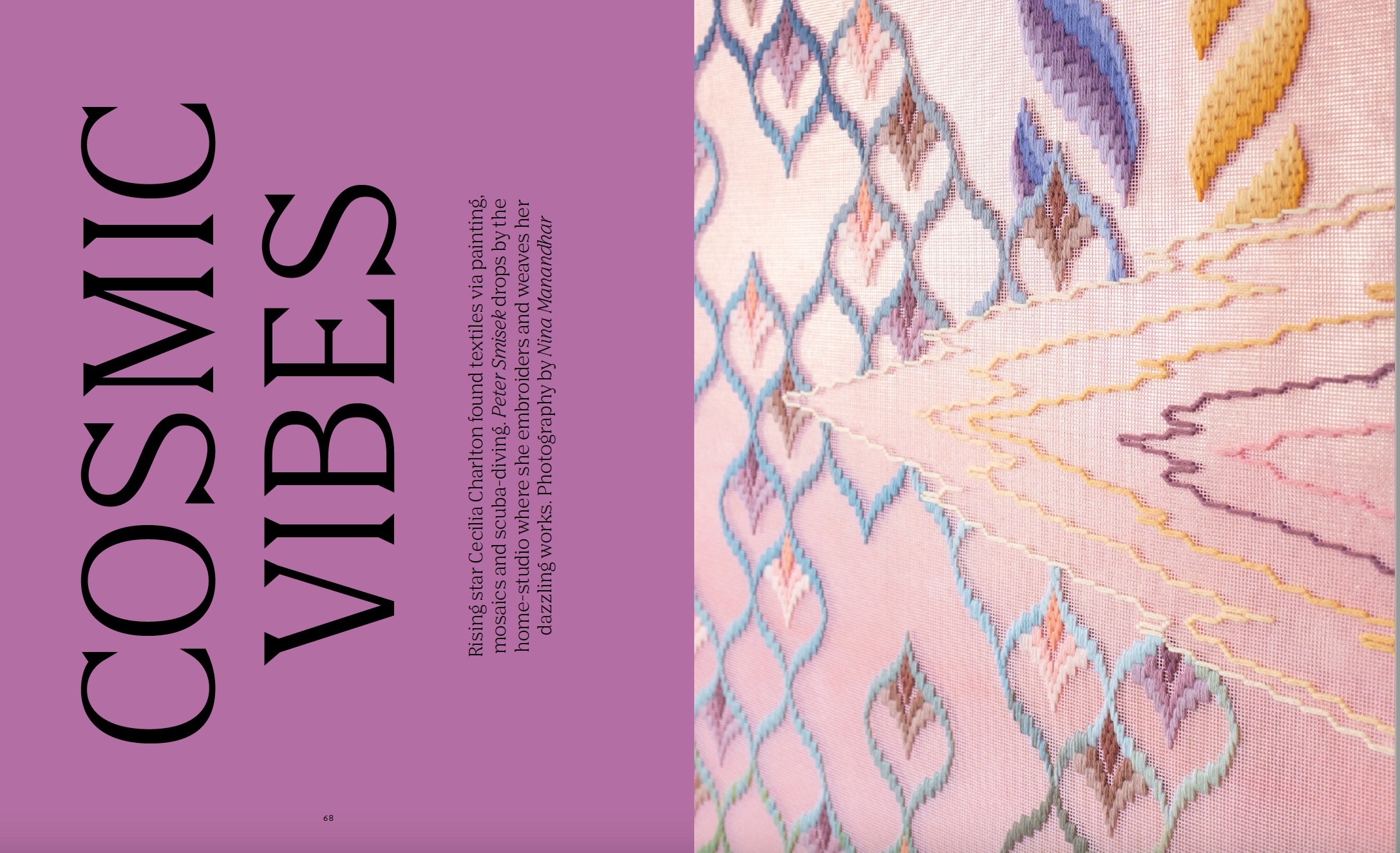

Rising star Cecilia Charlton found textiles via painting,

mosaics and scuba-diving. Peter Smisek drops by the

home-studio where she embroiders and weaves her

dazzling works. Photography by Nina Manandhar.

‘It’s an ouroboros kind of thing,’ says Cecilia Charlton, speaking of the circular path that

brought her to weaving – the ouroboros being an ancient symbol of a serpent eating

its own tail. Now one of Britain’s most exciting textile artists, she is chatting to me in

her south London home-studio on a misty February morning. Charlton is fast gaining

fame for her almost psychedelic woven wall-hangings, colourful geometric embroideries

and intricate pieces combining thread and paper.

‘My childhood was really framed around textiles as they relate to the domestic

sphere,’ she recalls, speaking of her childhood in Upstate New York. Her grandmother

was a prodigious quilter with a degree in textiles, and her mother is a ‘voracious’

knitter as well as a professional seamstress. Despite this, a career in craft didn’t seem

like an option at the time – it was just something the women in Charlton’s family did.

Instead, she tried to follow in her father’s footsteps by studying engineering, but quickly

realised this wasn’t the right fit.

From that point, Charlton slowly made her way back towards a more familiar

creative domain. She initially tried metalwork, followed by pottery, which instilled

in her a love of working in the studio; she was enamoured by the physical process of

making, and the alchemy of wood-fired glazes. But making ceramics, especially pieces

with a functional purpose, felt limiting when it came to pursuing the aesthetic she was

interested in, she says, explaining that her initial fascination was with making pots

with small feet that would sometimes topple over.

From there, Charlton enrolled at Manhattan’s Hunter College, and in a bid for

fewer practical constraints, she put pottery aside in favour of painting. Once again,

she delved into the studio, but now with a renewed interest in modern and contemporary

art. Alongside her sense of newfound freedom came the chance to apply to

London’s Royal College of Art – an institution with which her American alma mater had

a strong partnership. Her application for an MA in painting was successful, and with

her trans-Atlantic move came more opportunities for European travel. ‘When I went to

Italy for the first time, I saw the Byzantine floor mosaics at the San Mark’s Cathedral in

Venice and realised there were a lot of similarities with what I wanted to achieve in my

paintings. They used a lot of colour, but they were interested in composition, not just

pattern,’ she says. Today, using arrangements of patterning to explore light and colour

is a defining feature of Charlton’s work.

The change of medium – from acrylic paint to thread – happened in July 2017,

when Charlton realised she wanted the materiality of her work to manifest itself more

naturally. As she explains, in those Italian stone mosaics – as in embroidery and weaving

– the material becomes both the sign and the signifier, whereas paintings only

offer the satisfaction of surface representation. ‘I feel like there’s a presence about

the works that are made through weaving or through textiles processes, as opposed

to painting.’ Which brings us back to the front room of her Victorian flat, where her

countermarch loom now lives.

Her studio is just separate enough from domestic life to foster concentration

and contemplation, while allowing the artist to come and go as she chooses. ‘It’s so

valuable to me to be able to come and sit in here in the evening and just look at things,

even when I’m brushing my teeth,’ she explains. ‘I feel like that would be really hard to

replace – the accessibility and the immediacy of the relationship of what you do with

your studio.’

The shift from painting to textiles enabled Charlton to draw on her own family

history, but also to contextualise her practice within the long tradition of textile arts

– a history that, as she tells it, is both incredibly diverse and cuts across cultural and

gender divides. The widely held view of textile production as a tool of female oppression

is ‘a limited, relatively new western-centric perspective’, asserts Charlton.

‘There has also been quite a lot of female empowerment in the history of textiles. For

example, the recent research that has been published around Viking women funding

raids through their highly skilled weaving production.’

Of course, textiles were never a purely female domain, but Charlton says: ‘There’s

a view that when it comes to artisanal and domestic production, it’s for the women,

but when it enters the sphere of commerce, it becomes the domain of men.’ Such

comparisons are not unique to the world of craft – statistically speaking, women do

the majority of the housework and cooking even today, while many of the world’s

most famous chefs are still men, for instance. ‘The Jacquard loom was invented

by a man,’ she continues, pointing out that his invention helped automate weaving and

open the gates to industrial-scale production of cloth. ‘But then you have Ada Lovelace

coming in and integrating that logic into the first computers.’ This narrative, of

interdependence, of radical innovation across genders, countries and disciplines, is

something Charlton likes to foreground in her work. She sees textiles as inherently

communal, nurturing and inclusive, and chooses in her work to focus on stories of

individual and collective achievements across divides.

Her 2021 installation in Ilford, a corner of east London, for example, drew on

collaborative workshops with local residents. These included embroidery and fabric

dyeing, designed to produce works celebrating local history, centring on a mammoth

skull discovered in the area by archaeologists in the 19th century. The work also references

traditional American quilting techniques – bringing Charlton back to her roots

in folk textile traditions in the United States.

She has explored narratives of interdependence in her site-specific installation

for the London School of Economics’ new Marshall Building. Here, the link between

textiles and the world economy is symbolised through a trio of tapestries called Interaction

of pattern [systems of influence in red, green & blue], which hang dramatically in

one of the building’s main staircases. She uses the historical overshot technique that

was brought to North America by European settlers, complicating it through interferences

that merge together, referencing the interdependence of the world economy

– executed in that same medium, textiles, that did so much to drive capitalist expansion

and globalisation throughout the centuries. Despite their pixelated, digital-like

aesthetic, Charlton’s main technological tools are the needle, the loom and her hands.

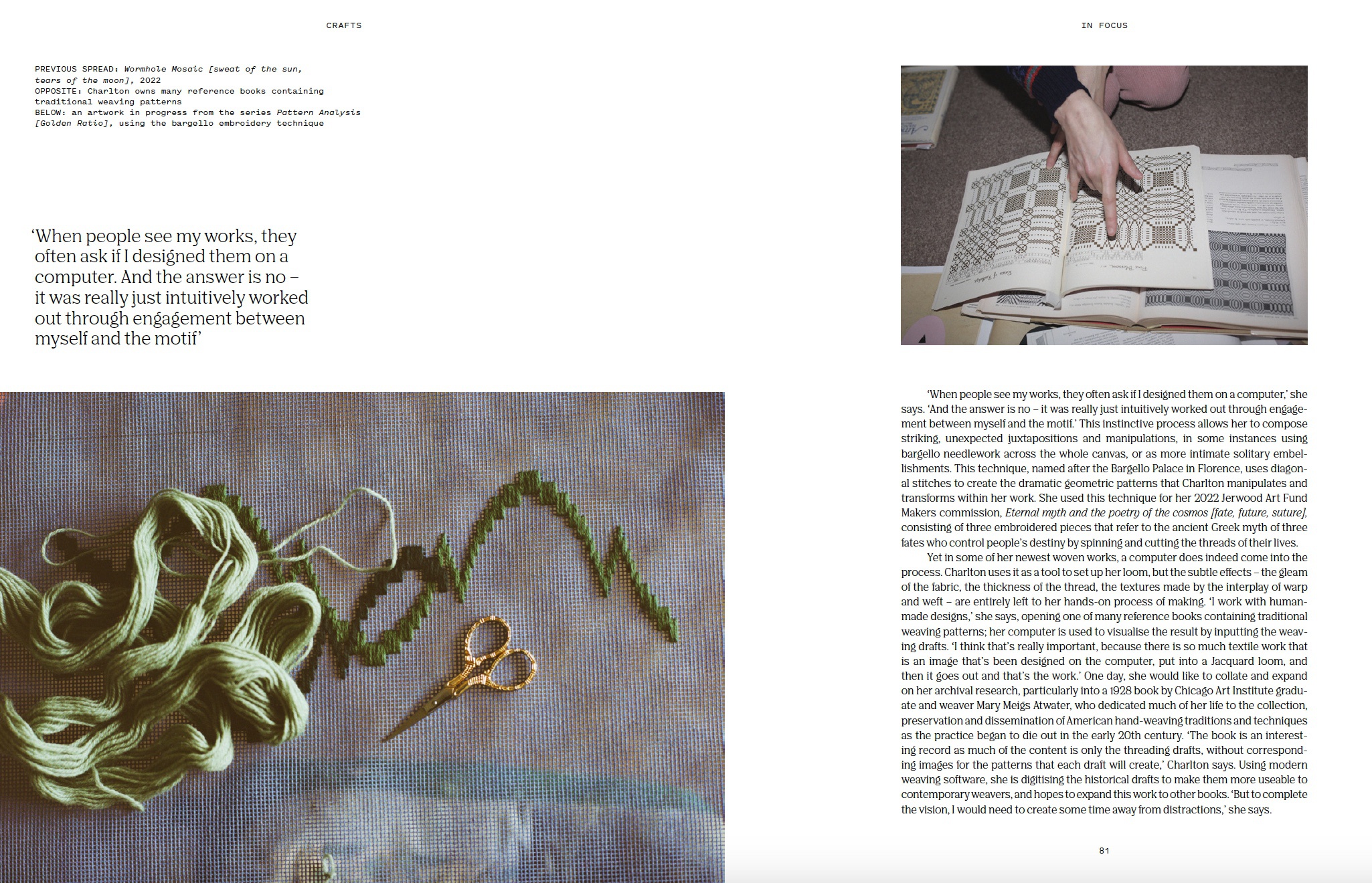

‘When people see my works, they often ask if I designed them on a computer,’ she

says. ‘And the answer is no – it was really just intuitively worked out through engagement

between myself and the motif.’ This instinctive process allows her to compose

striking, unexpected juxtapositions and manipulations, in some instances using

bargello needlework across the whole canvas, or as more intimate solitary embellishments.

This technique, named after the Bargello Palace in Florence, uses diagonal

stitches to create the dramatic geometric patterns that Charlton manipulates and

transforms within her work. She used this technique for her 2022 Jerwood Art Fund

Makers commission, Eternal myth and the poetry of the cosmos [fate, future, suture],

consisting of three embroidered pieces that refer to the ancient Greek myth of three

fates who control people’s destiny by spinning and cutting the threads of their lives.

Yet in some of her newest woven works, a computer does indeed come into the

process. Charlton uses it as a tool to set up her loom, but the subtle effects – the gleam

of the fabric, the thickness of the thread, the textures made by the interplay of warp

and weft – are entirely left to her hands-on process of making. ‘I work with humanmade

designs,’ she says, opening one of many reference books containing traditional

weaving patterns; her computer is used to visualise the result by inputting the weaving

drafts. ‘I think that’s really important, because there is so much textile work that

is an image that’s been designed on the computer, put into a Jacquard loom, and

then it goes out and that’s the work.’ One day, she would like to collate and expand

on her archival research, particularly into a 1928 book by Chicago Art Institute graduate

and weaver Mary Meigs Atwater, who dedicated much of her life to the collection,

preservation and dissemination of American hand-weaving traditions and techniques

as the practice began to die out in the early 20th century. ‘The book is an interesting

record as much of the content is only the threading drafts, without corresponding

images for the patterns that each draft will create,’ Charlton says. Using modern

weaving software, she is digitising the historical drafts to make them more useable to

contemporary weavers, and hopes to expand this work to other books. ‘But to complete

the vision, I would need to create some time away from distractions,’ she says.

‘ When people see my works, they

often ask if I designed them on a

computer. And the answer is no –

it was really just intuitively worked

out through engagement between

myself and the motif’

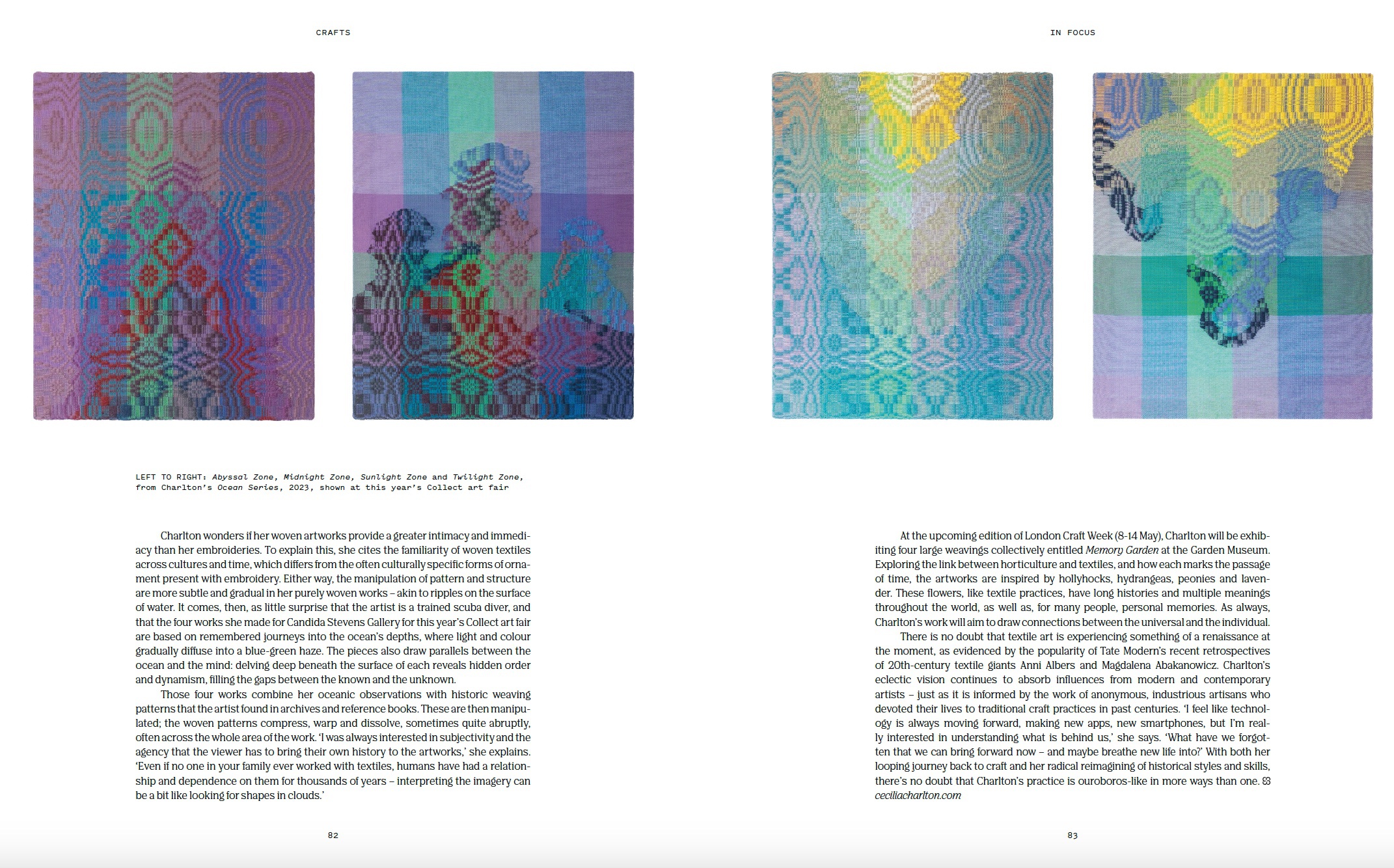

Charlton wonders if her woven artworks provide a greater intimacy and immediacy

than her embroideries. To explain this, she cites the familiarity of woven textiles

across cultures and time, which differs from the often culturally specific forms of ornament

present with embroidery. Either way, the manipulation of pattern and structure

are more subtle and gradual in her purely woven works – akin to ripples on the surface

of water. It comes, then, as little surprise that the artist is a trained scuba diver, and

that the four works she made for Candida Stevens Gallery for this year’s Collect art fair

are based on remembered journeys into the ocean’s depths, where light and colour

gradually diffuse into a blue-green haze. The pieces also draw parallels between the

ocean and the mind: delving deep beneath the surface of each reveals hidden order

and dynamism, filling the gaps between the known and the unknown.

Those four works combine her oceanic observations with historic weaving

patterns that the artist found in archives and reference books. These are then manipulated;

the woven patterns compress, warp and dissolve, sometimes quite abruptly,

often across the whole area of the work. ‘I was always interested in subjectivity and the

agency that the viewer has to bring their own history to the artworks,’ she explains.

‘Even if no one in your family ever worked with textiles, humans have had a relationship

and dependence on them for thousands of years – interpreting the imagery can

be a bit like looking for shapes in clouds.’

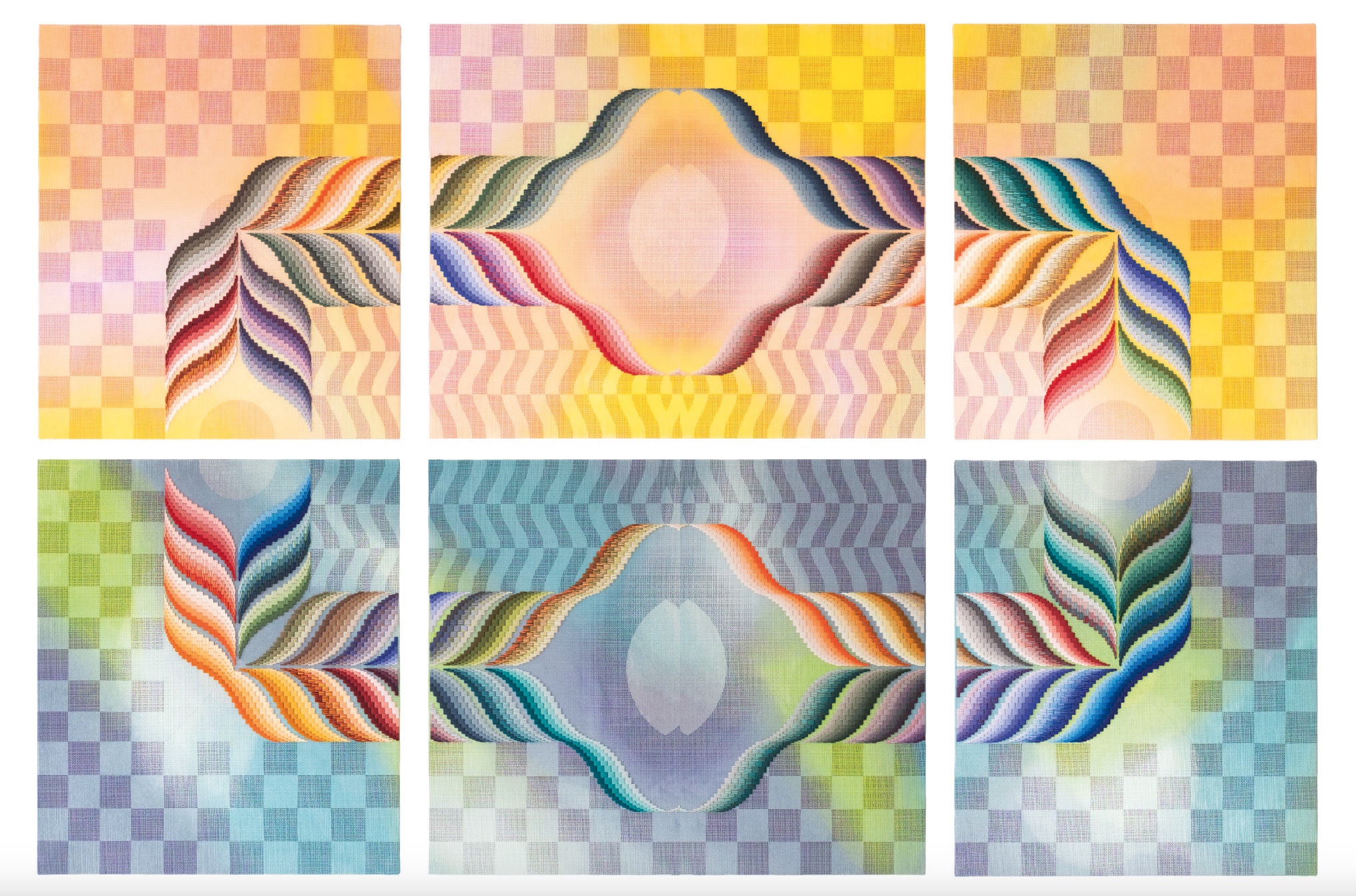

At the upcoming edition of London Craft Week (8-14 May), Charlton will be exhibiting

four large weavings collectively entitled Memory Garden at the Garden Museum.

Exploring the link between horticulture and textiles, and how each marks the passage

of time, the artworks are inspired by hollyhocks, hydrangeas, peonies and lavender.

These flowers, like textile practices, have long histories and multiple meanings

throughout the world, as well as, for many people, personal memories. As always,

Charlton’s work will aim to draw connections between the universal and the individual.

There is no doubt that textile art is experiencing something of a renaissance at

the moment, as evidenced by the popularity of Tate Modern’s recent retrospectives

of 20th-century textile giants Anni Albers and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Charlton’s

eclectic vision continues to absorb influences from modern and contemporary

artists – just as it is informed by the work of anonymous, industrious artisans who

devoted their lives to traditional craft practices in past centuries. ‘I feel like technology

is always moving forward, making new apps, new smartphones, but I’m really

interested in understanding what is behind us,’ she says. ‘What have we forgotten

that we can bring forward now – and maybe breathe new life into?’ With both her

looping journey back to craft and her radical reimagining of historical styles and skills,

there’s no doubt that Charlton’s practice is ouroboros-like in more ways than one.